In second grade, I was new to my school—and my school district—even though we hadn’t moved and the district boundary lines hadn’t changed. What happened was that I had been a “mid-termer” the year before.

A few months into second grade, Mom said, “Mrs. Floyd was wondering if you’re having trouble seeing the board. Are you?” “No, Mommy. I can always see the board.”

Having a December birthday, I was not going to be permitted into first grade in our school district, which served a lot of “unincorporated” neighborhoods outside the city boundaries, until the fall after I turned six. But Mom could see that would be too long to wait. I was more than eager (and ready) to start school sooner than that. She found out that in schools serving the city of Indianapolis, just a couple miles away, they had something called mid-termers. These were children who began first grade (and subsequent grades) around the end of January or early February.

Looking back, I am curious to know what these kids did once they got to high school, as it strikes me as impossible for a school to organize foreign language instruction and advanced math and all the other classes that would be needed on both the “regular” and the “mid-term” cycle. I never found out because I was a mid-termer only in first grade, and the concept of “mid-termers” as an educational practice does not yield any results in my Internet searches.

The city school allowed Mom to register me as a first-grade mid-termer, so long as she could bring me and pick me up. (The other children walked to and from school and nearly all also walked home for lunch.) I assume there was also a fee involved, since my family’s local taxes went to the county, not the city.

I was the only kid who had to wait outside every day to be picked up. That was tough. One afternoon I saw an aqua-colored Ford station wagon already parked as I exited the building and breathed a sigh of relief that I wouldn’t have to wait at all. I walked to the passenger side and as I slipped in, realized that nobody was in the driver’s seat and Mom must have gone into the school to find me. I decided to just wait for her to return to the car. As I sat and waited (there were no booster seats or rules about kids my size and age sitting in the back in 1955), I looked around and was surprised to observe a bunch of cracked peanut shells and some candy wrappers in and around the ash tray. It slowly dawned on me that my mother would not be eating candy and nuts and in fact, this was not our car! I got out and went back to the sidewalk and sure enough, within moments, mom pulled up in the Ford station wagon. The right one. I doubt if if I told her I had just gotten into the wrong car.

1954 Ford Ranch Wagon Sea Foam Green. Pretty close to the model I was watching for every day after the others walked home.

It was not an easy year. The lunch tables for the younger kids who weren’t going home for lunch were supervised by older students, probably eighth graders. They weren’t very friendly. And the lunches consisted of a lot of gooey and runny things that slid into each other. I preferred that my meat not touch my potatoes and that my potatoes not touch my vegetables (or that they just leave out the vegetables). But on the bright side, my first-grade teacher taught us to draw birds, and an elephant placing one foot on a low stool, and some other animals. I can still do the elephant.

One day, Mrs. Peterson asked us to draw a picture of a duck floating on the water, and I proudly colored in the blue water with little rippling waves that kids learn how to make, and then on top of that a duck in yellow, upside down, with its orange webbed feet sticking straight up into the air.

I’m not sure what my teacher thought of it. But my parents wanted to know, when I brought it home, why the duck was “upside down.” “That’s not ‘upside down,’ I admonished them. That’s how you float.”

“Why not with the feet down under his body?” Dad wanted to know.

“Well, if you float with your face down and your back up, that’s called a ‘dead man’s float.’ I would have done it that way if she asked for a duck doing a dead man’s float. But she didn’t. She said a duck floating.” That seemed to bring an end to the questions.

After one semester as a mid-termer at IPS School 59, I was back in my home school as a second grader.

Somewhere around this time, I took an IQ test. I doubt that the Indianapolis Public Schools would have required it; more likely it was required by Washington Township in order to admit me into second grade after completing only one semester of first grade in another district.

In any event the IQ test is one of my earliest detailed memories. Mom was sitting nearby at a table in a classroom, while a male tester who had no memorable attributes presented me with various challenges. I was supposed to sort a series of four cartoons into the right sequence. Honestly, I had no idea, and I can still remember how aware I was of being clueless. Decades later, I would come to realize that my visual literacy had been low since childhood, and I started working consciously to improve it.

The images presented consisted of a man with a suitcase outside a train station, inside a train station, at a ticket window, and at a large scale. I was able to say something about him going on a trip, and perhaps that he wanted to know how much he weighed. I know I got them in the wrong order.

For the vocabulary, the tester asked me to explain the difference between an ocean and a river. I am certain I took quite a pause as I needed time to think it over, but then stated with some confidence, “Boats go on a river, and you swim in the ocean.” I’m not sure what the tester was expecting on that one. To me, it still seems pretty good.

If the test had something to do with my entering Fall Creek School in second grade, then evidently, I scored in the acceptable range. I was happy to now be getting on the bus and going to the same school where my brother was going—one grade ahead of me, although he was two years older. But in my classroom, I remember feeling for a while just as much the outsider as I had in first grade. The kids at School 59 mostly lived in the same neighborhood and knew one another. The kids at Fall Creek had already been socialized to the mores and routines and many had been in the same first grade class.

Recess was a particular challenge—or more specifically, the end of recess. We were allowed out the back door of Mrs. Floyd’s classroom and then everyone went helter-skelter all over the place, from the stone-covered playground with various swingsets and slides to the grassy fields where some kids just ran around. There was a lot of space, and there were kids from a whole lot of classes out there at once, not just the other second grade classes but from some other grades as well.

I don’t recall anyone orienting me to the ending routine of recess, but it seemed that teachers stood near their classrooms and one of them blew something like a referee’s whistle. (Not that I would have known to call it that at age six.). Kids started lining up in single-file in the line that had their own teacher in the front. But how could they possibly tell which one was their teacher from that far away? I remember being really worried that I would get in the wrong line. I’m sure I did get in the wrong line in those early days, and had to be steered right.

Winding up in the wrong line would explain why I decided to just follow Paul Ford—a classmate I liked who also lived a couple streets away and rode the same bus in the morning. I would follow him around during recess, and that way, when the whistle blew, I would get in the line he got in! Bingo—no more having to recognize Mrs. Floyd from halfway across the playground; no more feeling dumb because I got in the wrong line. I might not have a very fun time at recess—watching Paul running around with his friends, swinging on the swingset with his friends. But I didn’t have any friends yet anyway, and at least I would know when and where to line up.

Most likely, my difficulties in recognizing which line to join was influenced by the beginning stages of my myopia—but that wouldn’t occur to me until about 40 years later. At the time, I felt so impressed that just about all the other kids could tell just where to line up! Wow! How did they do that? I probably just thought it was a skill they picked up–recognizing a teacher’s face through the haze, the fog, the distance–while I was over at School 59, learning how to draw birds and elephants, and eating gooey food.

A few months into second grade, Mom said, “Mrs. Floyd was wondering if you’re having trouble seeing the board. Are you?” “No, Mommy. I don’t know why she would say that. I can always see the board.”

Another couple of weeks went by. “Mrs. Floyd spoke to me again. She says she moved you to the very front row of the class because you were squinting and having a hard time reading what’s written on the board.” “Yes, that’s right.” “That’s right? You mean you have been having a hard time reading what’s on the board?” “Yes, Mommy.”

“Dale, didn’t I just ask you about this a couple weeks ago and you told me you could see everything just fine?” “No, you asked if I had trouble seeing the board. I can always see the board. I just can’t see what she’s writing on the board.”

I guess the duck should have given it away the year before. But that’s when I got a reputation in my family of “taking everything literally.” But it’s also when I got eyeglasses.

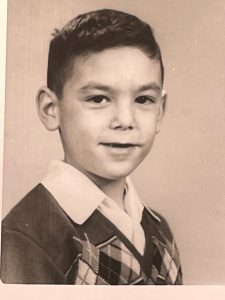

I was so nervous, coming into Mrs. Floyd’s class with my newly acquired glasses with dark plastic frames. I was still feeling a bit like a “new kid,” since I wasn’t with these kids in first grade. I was worried that kids would make comments and I wouldn’t know what to say. Sure enough, I had no more than entered the classroom when some girl—maybe Penny Fortune, that blonde girl who was usually at the top of the reading chart–called out, “Dale, you’re wearing glasses! Oh my gosh, where did you get those?”

It was my worst nightmare. Kids asking me about my glasses, and I had no idea what to say in response, how to repel the shame and embarrassment of it all. Fortunately, there was one other kid in the class, Don Harding, who already wore glasses. He was one of the taller boys too, and a little cocky—not like me, younger than anyone in the class, and shy. He barged right into the conversation. “Where do you think he got ‘em? At the glasses store!” After that intervention, nobody else said a thing, and Don Harding had a fan for life.

Dale Borman Fink retired in 2020 from Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, MA, where he taught courses related to research methods, early childhood education, special education, and children’s literature. Prior to that he was involved in childcare, after-school care, and support for the families of children with disabilities. Among his books are Making a Place for Kids with Disabilities (2000) Control the Climate, Not the Children: Discipline in School Age Care (1995), and a children’s book, Mr. Silver and Mrs. Gold (1980). In 2018, he edited a volume of his father's recollections, called SHOPKEEPER'S SON.

Dale, thanks for such an interesting memoir about your early grade school years. I recall a lot of kids worry about wearing glasses, and some went to the nth degree to keep from doing it. One comment you made in there that brought the cafeteria experience back to me immediately was the description of food as being so “gooey and runny that slid into each other.” Yep, that was grade school!

This is a cute story, Dale, although I empathize with your anxiety over being teased because of glasses. Glad you had a savior. Interesting how we compensate for “deficiencies,” as you did by following the other boy around, not being aware that your eyesight was the issue. BTW, my niece was a “mid-termer” because of her January birthday, but it was easier for her because she spent that awkward time in kindergarten and then went on to the standard first-grade class.

Thanx Dale for giving us a windw into your 1st and 2nd grade life.

I am always amazed at your powers of recall and detail, and can clearly see little Dale with his new eyeglasses. And so thankful for that fellow eyeglass-wearer who befriended you saved the day!

Dale, you’ve met another “mid-termer”. I also have a December birthday and Detroit started all of us in Feb, so we were all half-way through a grade (my elementary school was K-8). At that point, everyone went to summer school to make up the semester before starting high school, but my family moved to the suburbs when I was half-way through 5th grade. I was smart (tested at 10th grade reading level in 3rd grade), so I was tutored for 4 weeks in math and just moved ahead to 6th grade. But the new school was K-6, so the 6th graders were the kingpins of the school, had all been together forever, were much more sophisticated than I was and teased me terribly. I could do the work, but socially, it was a horrible year for me. So that’s what happened to this mid-termer (you can read more about it in the “betrayal” prompt).

And just like you, I began wearing glasses at the age of 8, when I couldn’t read the board. Like you, I was teased about that too, though my teacher was a wonderful woman and mentor to me, so it wasn’t too awful at the beginning.

I love how literal you were in responding to your mother’s query. I have several people in my life like that. I understand entirely! It all worked out for both of us, eventually.

What a valuable response, Betsy! Now after all these years, I understand what the procedure would have been, eventually, for a midtermer to rejoin the ranks of the “regular” students. So happy to meet “another one.” Sorry to hear about your transition when you went up to 6th grade in the suburbs.

Finally, I’m glad you have learned to accommodate those of us who are literal-minded. I imagine it could be frustrating, but we don’t do it on purpose!

Wow! There’s so much here, Dale, and so well expressed. I marvel at your memory.

I. too, like you and Betsy, had the mid-term experience. But mine was a bit unusual. I started in September for kindergarten but after fourth grade I and three others skipped the first half of fifth grade. The mid-term arrangement facilitated that. But when I went away to school in ninth grade I wound up repeating the first half of the grade, which was useful given the higher rigor of the school. Some of my former classmates accelerated their high school work to graduate six months early; some let things lie and worked for six months before college.

And the notion that you took things literally, well, why shouldn’t you? It is what it is. The classic example is the answer to the question, “are you a boy or a girl?” The only correct answer is “yes”.

I love the literalism you provide at the end of your comment. As to your experience as a mid-termer-very unusual. You’re telling me that some kids maintained the midterm anomalous status all the way through high school and graduated in the middle of the year? I still don’t get how secondary curriculum could be efficiently organized around such a system!

BTW, did you also grow up in the Midwest like Betsy and me? Where was it that you joined the notorious “M-T” squad?

No, I grew up in upstate New York. And as for deployment of resources, in grade school there was a cadre of teachers who taught regular termers and a second, smaller contingent for mid-termers. In junior and senior high school the same faculty taught both sets, simultaneously teaching the first and second halves of the curriculum.

As I write this I recall an anecdote. Throughout the twelve grades the first semester of the curriculum was “B” and the second was “A”, so a regular term fourth grade student would start 4B in the fall, a midtermer in February. We had a transfer student from Philly in third grade who came from a similar environment except that they reversed the nomenclature. It took a few weeks before our school realized what happened and placed him correctly.

Nice that you had a glasses-wearing ally and champion!

My parents had a term for kids who said stuff like your literal answers to questions….

I’m sure that Retrospect readers would love to know what that term was that your parents applied to kids like me! Unless it’s too profane.

I love that you said yes, you could see the board. Makes perfect sense to me. She didn’t ask if you could read what was written on the board. Also love that you got in the wrong aqua station wagon, and figured out your mistake because of the detritus around the ashtray.

I’m enjoying the discussion in the comments about midtermers. I knew Betsy was one, and I thought of her immediately as soon as I read your first two paragraphs. They didn’t have that in New Jersey, although I moved from 2nd to 3rd grade in the middle of the year. But the next year I went on to 4th grade with all the other kids in my 3rd grade class.

Good job. I had fun reading it, especially the angle about taking things literally, since I’ve been known for the same problem. I confess I have even used the tendency disingenuously (passive-aggressively) at times…

Gotta love that duck, Dale! And the oozing lunch. Brilliantly sum up the possibilities and dread of those early school days. Not to mention the metaphor of navigating myopia and the “otherness” of the glasses that bring everything into focus. Thank you!

Jan, the duck was the emotional peak of the narrative (to me) so thanks for that affirmation!