To my restless teenage soul, the University of California at Berkeley sounded like heaven. It was 1968, I was stuck in the bland, conservative desert of West Covina, Calif., and when I pondered college I couldn’t imagine a more comfortable fit than the seat of the student antiwar movement.

“There was a sense of exhilaration,” my friend Wesley remembers, “a feeling that we were reacting as a group, as one. That was a really intense, positive thing.” I believe the emotions and commitment generated that day forever altered the spirit and culture of Humboldt State.

Things didn’t work out that way. My father was appalled at the idea of my enrolling at a hotbed of radicalism, and since I lacked a scholarship or alternate source of tuition income I had to come up with another plan. I pulled out a map of California, studied the location of every state university and chose the campus farthest from home – Humboldt State, 700 miles north of West Covina.

HSU was located “Behind the Redwood Curtain” in Arcata, a sleepy, fog-bound town of 8,000 people. Seemingly locked in a political and cultural time warp, Arcata had two TV channels and two radio stations. The local logging industry still thrived, a redneck element actively disliked the campus community, and the only restaurant of note was a greasy spoon called Tracy’s that served bilge for coffee and grunts for service.

I’d been on campus a week or two when I attended my first demonstration. Ronald Reagan, then governor of California, was meeting with local Republicans at the Carson Mansion, an elaborate Victorian in nearby Eureka. There were 20 or 30 of us on the picket line, shouting slogans and holding placards. We had plenty of reasons to be angry: Reagan had slashed education and mental health spending, authorized police brutality against campus protesters, and alienated environmentalists with his classic remark, “If you’ve seen one redwood tree, you’ve seen ‘em all.”

Reagan was slick, but underneath that cheery veneer was a politician who made decisions that were hard-nosed and callous. I remember him pausing to wave at us malcontents as he entered the Carson Mansion — very little security detail that day – and flashing that fixed Hollywood smile as we shouted our disapproval.

Naively, I went back to my dorm room and wrote my parents a detailed letter describing the protest and the content of the slogans and placards. What was I thinking? Just plain dumb, or maybe I was hoping to tweak my Dad’s ire. Predictably, the letter I got in return (“I am very perturbed”) made it clear that my college allowance would end if I continued to disport myself in such an imprudent manner.

Not that opportunities for political dissent abounded at Humboldt State. The political fervor of San Francisco, Berkeley and Oakland was 300 miles away and in Arcata it was easy to feel cut off from the world. Over the next year and a half, that sense of remoteness and disengagement would change dramatically.

My college years, 1968 to 1972, were a time of historic tumult and division in America — but also a time when we felt excited by the possibility of profound change. Nixon kept escalating a corrupt, horrendous war. In November 1969 we learned that U.S. troops had massacred up to 500 Vietnamese civilians in the village of My Lai. In May 1970 Nixon bombed Cambodia and colleges erupted in angry protests. When four unarmed students were killed by the Ohio National Guard at Kent State University in Ohio, hundreds of campuses nationwide went on strike.

Humboldt State was one of them. The day of the Kent State shootings, a spontaneous forum was held in the Sequoia Theater where people shouted their rage and struggled to formulate some kind of cogent response: “What can we do?”

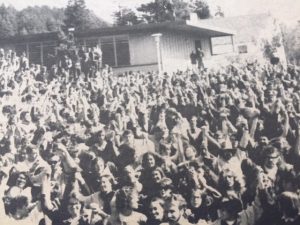

The next day a much larger rally took place on the campus quad between the music, art and theater buildings. An amazing event. “There were three to four thousand people there,” my friend Wesley Chesbro, who later became a California state senator and assemblyman, remembers. “Standing on the rooftops. You could hardly squeeze into the plaza.” Speeches were made, draft cards were burned, a magnificent singer named Becky Evans brought out her guitar and lifted everyone’s hearts. People remained for hours, focused and intent. Anyone who wanted to speak was given a chance. At the end of the rally a vote was taken: Should we call for a campus-wide strike? The vote by hand was near-unanimous.

It was a passionate, soulful, unforgettable day – unlike anything previously seen at HSU. Prior to that, our only campus activists were a tiny, far-left faction who generated little support for their actions. But on that sunny afternoon in 1970 I remember a kind of collective frisson and excitement. An awakening.

“There was a sense of exhilaration,” my friend Wesley remembers, “a feeling that we were reacting as a group, as one. That was a really intense, positive thing.” We had a common purpose that day, and I believe the emotions and commitment generated at that rally forever altered the spirit and culture of Humboldt State.

The momentum continued. Northtown Bookstore, located two blocks off campus, became strike headquarters. Hundreds of people committed to walking precincts to convince local residents to oppose the war. A lot of them were longhairs who got their first haircut in years in order to interact with the community. One of the strike honchos, Lanny Swerdlow, asked me to organize a teach-in at the local Presbyterian Church. I’d never done anything like that before – I was 19 – but I booked the speakers, moderated the event and was amazed when locals and parishioners showed up to ask questions and in some cases voice their opposition to our movement.

Cornelius Siemens, president of the campus, did a crafty thing by endorsing the campus strike – thereby deflecting any anger that might misdirect toward the campus. He even joined a small coalition that flew to Washington, D.C. to lobby our legislators to end the war in Vietnam.

Dr. Siemens was less than thrilled with the memorial bomb crater that a Vietnam Veterans Against the War group created just outside the administration building. The vets dug an enormous hole and erected a sign explaining that their purpose wasn’t to destroy university property but to make a statement. They carefully separated the topsoil from the subsoil, so the lawn could be properly restored when the strike was over – but that effort was foiled when a bunch of pro-war campus jocks angrily refilled the crater, shoveling the topsoil in first with the subsoil layered on top.

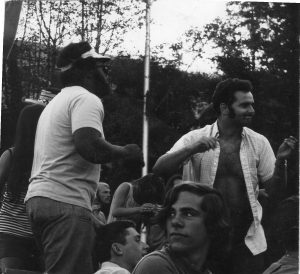

At Peace Days festivities at Humboldt State, 1970. I’m in the lower part of the frame, looking toward the left.

The war raged on for another four years and Nixon somehow was re-elected in 1972, but Humboldt State had effectively rubbed the sleep out of its eyes. The campus, once obscure, became known as an alternative haven for lefties, artists, potheads and Deadheads — in addition to forestry, wildlife and oceanography majors. Admission applications soared. Arcata had a new civic pride and cultural birth with restaurants, a nightclub or two, two repertory cinemas and a city council now dominated by progressives and not the pro-timber, anti-hippie old guard. The town opened one of the nation’s first municipal recycling centers, and converted a solid-waste dump on Humboldt Bay into the Arcata Marsh & Wildlife Sanctuary, a network of freshwater and saltwater ponds, tidal sloughs, mudlflats and walking paths.

Although I felt like I’d been dropped into an earlier decade when I first arrived in Arcata — like a character on “The Twilight Zone” — I later realized how lucky I was to witness such dynamic, thrilling change in a short window of time. Instead of the hard-edged politics of Berkeley during that same era, I was part of a gentler, more balanced activism that encouraged community instead of rancor and division.

Amazing retelling of the birth of movement, Edward. I liked the detail of the long-hairs getting hair cuts to interact with the community. I’m not sure going forward that many would have been so savvy. You might not have wound up at Berkeley, but you got to witness and shape your own political movement and be right at its epicenter. Thank you for sharing its details.

Thank you for this brilliant retracing of Reagan’s legacy and the cultural history of Arcata. I liked it when I visited there and this makes me want to move there.

Thank you, Victoria!

Edward, what a wonderful story to have just discovered! Hopefully it appears elsewhere as well…it’s something that should be and hopefully has and will be read by many.

I also like your photo caption…looking toward the left. Indeed, and bravo!

Thanks very much!