Interviewing Gregory Peck in 1989. A favorite memory from a career in journalism.

By Edward Guthmann

I wanted to capture the roaring, rude dynamism of the late ‘60s and early '70s, a world in flux – not as it appeared from a distance to a disinterested newsman, but as someone immersed in the zeitgeist.

I was born curious. Curious to a fault, my parents said. So curious that to this day people say, “Wow, you sure ask a lot of questions. I can see the journalist coming out in you!”

I get their point, but in fact that all happened in reverse. I didn’t start asking questions because journalism taught me how. Rather, I became a journalist because my innate curiosity was already intact.

In my sophomore year of high school I joined the campus newspaper, the Spartan Shield. I liked interviewing people and writing about them, hanging out with my fellow cub reporters. We did everything: pasted up pages, sold ads, wrote features and editorials and followed the direction of our wonderfully peculiar faculty advisor, Mrs. Martha Lupton Schneidewind.

Generous, bawdy Howard Seemann, right, was my mentor at Humboldt State. Pictured here with journalism profs Alann Steen and Mark Larson.

Still, I didn’t see journalism as a career and when I enrolled at Humboldt State University near the Oregon border I declared a Psychology major. I figured since people were fascinating to me — Why does that person do that? — it was a perfect fit. But psychology, at least as presented at Humboldt State, was more about lab rats and statistical methodology than the wormy mysteries of the human psyche. By the end of my freshman year I changed my major to journalism.

HSU had a tiny journalism department, run by the pipe-smoking, stiff-shouldered Mac McClary and the Falstaffian, warm-hearted Howard Seemann. We learned the elements of reporting and the inverted pyramid style; studied copy editing and photojournalism, ethical principles and First Amendment rights. I shed a lot of bad writing habits, learned the value of concision and fact-checking — but I never got comfortable with the restrictive, old-school conventions of journalism.

Joan Didion, an early favorite of mine and a key figure in the New Journalism that expanded and enriched the parameters of journalism.

I was a child of the ‘60s, drawn to open vistas and experimentation, and the way journalism was taught back then felt formulaic. The curriculum emphasized an unbendable mandate of objectivity – Keep yourself out of the story; don’t get emotionally involved – while I was drawn to the bold, first-person expression of New Journalism heroes Hunter S. Thompson, Joan Didion and Tom Wolfe.

I wanted to capture the roaring, rude dynamism of the late ‘60s and early ’70s, a world in flux – not as it appeared from a distance to a disinterested newsman, but as someone immersed in the zeitgeist. I remember finding a quote from Ken Kesey, explaining the reason he quit writing, that perfectly captured my conundrum: “I’d rather be a lightning rod than a seismograph.”

I also knew that I wasn’t cut out, in terms of my interest and my temperament, for the life of a straight-on news reporter. Covering fires and City Hill intrigues? No thanks. I was a feature writer, a portraitist you might say, and that urge was little served by Humboldt State’s journalism curricula at that time.

By the time I graduated in 1972, I had soured on a career in journalism. I didn’t apply for a newspaper job, as many fellow grads did, but decided to explore and roam and find myself. I’d been in school my entire life, and it was such a different time: I didn’t feel the urgency and financial pressure that college graduates feel today. For many of us, career and financial security weren’t as paramount as finding your bliss and means of expression, your place in the world.

Ken Kesey, author, Merry Prankster and cultural force. When he quit writing he said, “I’d rather be a lightning rod than a seismograph.”

So I moved to San Francisco. I lived initially in the Haight Ashbury, later in the Mission district, and found work as a graphic artist in the garage of a couple living in Brisbane, a dull suburb south of the city.

After a year or two of typesetting and paste-up – the pre-computer tools of graphic arts – I got an itch to tell stories again. Gradually, that itch got bigger and in 1975 I became a full-time freelance journalist. Me, my manual typewriter, a coffee maker and four walls. I was drawing $52 a week in unemployment insurance, paying $130 per month for a studio apartment in south Berkeley. It was rough. Eventually, as the rejection slips mounted and I got tired of brown rice and veggies, I went back to graphic arts to supplement my writing income. The theater reviews I contributed to the Berkeley Gazette brought $25 apiece!

Ultimately, on the strength of several pieces I’d freelanced, the San Francisco Chronicle hired me as a staff writer in 1984. I was there 25 years, first as an arts & entertainment reporter and then as a movie critic. It was a glamorous job with a lot of cache: in addition to reviewing movies, I interviewed stars and directors, traveled to film festivals, profiled childhood heroes like Lucille Ball and Gregory Peck. People said I had the greatest gig on earth. But after 12 years of watching 200 movies per year, many of them absymally bad, I needed a gust of fresh air.

When I burned out as a critic in 2003 I segued to profiling authors, artists and diamonds in the rough. A man who survived a lobotomy at age 12 and spent his life healing from the abomination; an artist afflicted with acute photosensitivity who can’t go outdoors; an elegant English poet who died from methampethamine addiction; an 87-year-old grandmother whose gorgeous memoir of her Iowa childhood became a New York Times 10-Best-of-the-Year pick. I loved getting off the movie beat and doing human-interest pieces; it was the kind of journalism I’d wanted to do all along.

John Kapellas, a San Francisco artist with acute photosensitivity. He’s the subject of a profile I wrote, after I stopped reviewing movies.

In 2009 I started What I Do, a weekly series in which people sat with me and described their jobs. Unlike Hollywood celebrities, the people I profiled were unguarded, unmanaged and grateful to tell their story to someone who would listen. The Laotian immigrant shining shoes at Nordstrom; the 84-year-old riding the streetcar each day to her job at an office supplies shop; the safecracker and the San Francisco Opera prompter; the Salvadoran lady barber and the rock ’n’ roll drummer-turned-carpet cleaner.

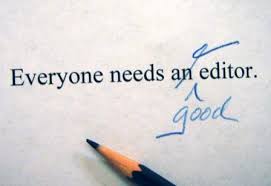

I love being a storyteller and a journalist, but I can’t say it’s ever easy. I often agonize over a piece, searching for the right language and tone, the perfect structure. I’ve had run-ins with editors who couldn’t see the value in a story idea I pitched, with copy editors who tried to standardize my writing and make it generic. I’m also grateful to the editors who gave me an extra push to make me braver; to the copy editors who fixed the occasional typo or factual error made in haste.

I’m also grateful to the editors who gave me an extra push to make me braver; to the copy editors who fixed the occasional typo or factual error made in haste.

Lots of journalists don’t study journalism in college. They come from other fields, and make the expertise of their original profession their journalistic emphasis. Conversely, many journalism majors don’t go into journalism: they become teachers or publicists or they get out of the communications racket altogether. It’s too hard and demanding.

I stayed. And I still yearn, each day, for a juicy, undiscovered yarn that’s begging to be told. Good journalism, like good fiction, binds us as human beings. It helps us to identify our feelings and makes us less alone.

Wow, Edward. This is an extraordinary piece. I know first- hand what a terrific interviewer and writer you are. Thanks for telling your own story here.

Edward, you have blown me away with this story. So beautifully written AND such a fascinating journey. I am glad that you went back to journalism after initially souring on the field. It would have been a shame to waste your talent. I wish I had been reading the Chronicle in the years that you were writing there.

I love Joan Didion too, and I have to mention that she grew up in Sacramento and went to the same high school as my kids. The house she lived in was recently up for sale, and I would have been sorely tempted to buy it if only I had been in possession of a spare million!

Fantastic and inspiring story, Edward. I’m awed by the deadlines and demands of daily journalism and so valued the work I did on my college newspaper (yes, paste-up, and I think I could still count proportional type for headlines). How you grew this career over your life is a treat to read.

What an extraordinary career. You did what I would have loved to do, but lacking the passion, nerve, and probably talent, I took a different path. I really admire your path and share your interest in a good story that makes a real human connection.