Chatham Village, 1966. I am eight years old and have recently watched the Miss America pageant—live from Atlantic City!—on television with Grandma Curtis. Grandma, a real shark when it comes to picking winners, says: “Miss California has the best figure, but she blew it in the talent competition. You can’t win with baton twirling if you don’t have flames. I’m voting for Miss Michigan—look at her in that white spangled evening gown. Elegant! Brains, beauty, and poise! Never underestimate the importance of poise. And her vocal interpretation of ‘June is Bustin Out All Over’ is divine.”

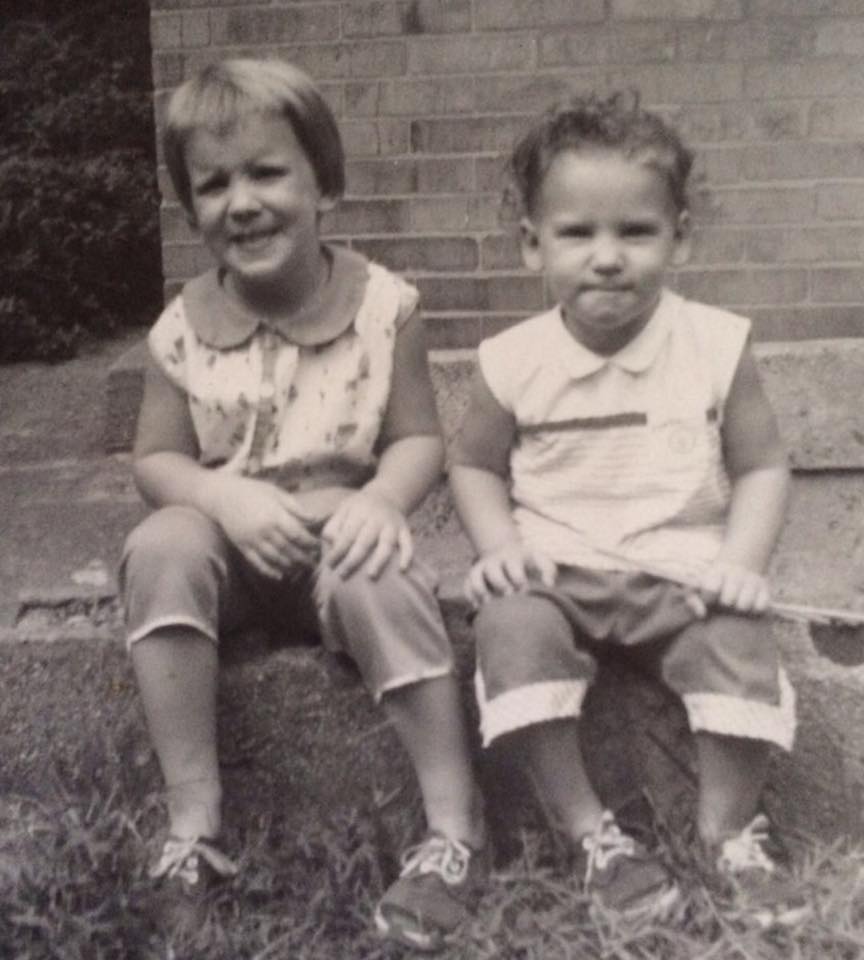

It is worth noting that my sister was born with coal black eyes and orange fuzz on her head. It is also worth noting that I have seen her bite a worm in half and that her favorite game is called "Let's Go Die."

Grandma Curtis is almost right. Miss Michigan doesn’t win the title, but she gets as far as first runner-up. I am intrigued by the concept of first runner-up. Almost good enough to win, but not quite. All of the work, none of the glory.

Some months later, my sister, Randy, and I decide to stage our own spectacle—the first annual Miss Chatham Village beauty pageant. Chatham Village, an idyllic wooded enclave right smack in the middle of Pittsburgh, features colonial brick town-homes surrounding lush green courtyards. Randy and I live in the upper court of the oldest part of Chatham Village, a perfect place for a long runway and a makeshift stage.

We gather a gaggle of our Village girlfriends, including the Marys—Mary Beth Wilson and Mary Helen Joyce; Alyce Amery, Kitty Engstrom, Lisa Hetrick, and the Loughney sisters, Casey and Lisa; the Clifford girls, Sharon and Sandra. Together we plot and plan the program and send crayola invitations to our parents, who usually spend their summer evenings sitting on front porches sipping drinks and grilling steaks. The Village could be the Pittsburgh setting for a John Cheever story: Wonderbread-ish, WASP-y, and two gin and tonics away from tennis-white perfect.

Problem: We need a judge for our pageant. We decide the last thing we want is a parental jury, or, worse yet, a panel of boys. What to do? Randy, seven years old and already a take-charge kind of gal, volunteers for the gig.

“I hate beauty,” she says. “And I hate swimsuits and evening gowns. And my only talent is chasing my brother with a baseball bat. I might as well be the judge.”

We agree. Randy will be the moderator and the jury—Bert Parks and the panel of experts rolled into one cocky little girl.

I think I’m a shoe-in because Randy and I share a bedroom and, on holidays, wear matching outfits with patriotic themes.

What’s this? All of the sudden, all of the pageant contestants are really nice to Randy. She gets extra cookies from our friends, extra rides on the backs of bicycles, extra turns on the Tarzan swing. I am too naive to understand the concept of a bribe, and the special treatment seems fair to me—after all, Randy has sacrificed her own chances of being Miss Chatham Village by volunteering to run the contest. I’m proud of my generous sister for stepping out of the spotlight so that the rest of us might shine.

It is worth noting that my sister was born with coal black eyes and orange fuzz on her head. It is also worth noting that I have seen her bite a worm in half and that her favorite game is called “Let’s Go Die.”

The day of the pageant arrives. Our parents collect in the courtyard and sit in assorted lawn chairs. Cocktails in hand, they chatter as Randy, barefoot, but wearing one of my dad’s bow ties, takes the stage to welcome the audience. She uses a stick wrapped in aluminum foil as a microphone.

“Please join us for the Pledge of Allegiance,” my sister says. This is not typical feature of beauty pageants, but I think it adds a nice touch. The adults rise, cocktails in one hand, heart in the other.

Randy begins introducing the contestants.

“Hailing from the lower court, Alyce Amery excels at math and reading. Her hobbies include coloring and going to the library.” Alice takes a long walk down the runway, wearing a frilly pink dress and flip-flops.

“From 610 Pennridge Road, Mary Beth Wilson attends St. Mary of the Mount school. She is a member of Stunt Club and—lucky for us!—enjoys singing. Unlike my father, Mary Beth’s father works during the day.” Mary Beth beams.

It goes on and on like this, with Randy introducing each of the girls competing for the title.

Then she gets to me, last on the list: “Here is Robin, better known as my sister.” That’s it? That’s all she says? I march down the runway, remembering what Grandma Curtis said about poise.

Because the pageant takes place fifty feet from our house, we use our living room for quick changes into swimsuit and talent costumes. The screen door squeaks and slams as we run back and forth. Meanwhile, Randy, hardly breaking a sweat, babbles on and on about each of us.

“And now, here is Mary Beth Wilson again, performing her version of Down in the Valley.” From the sidelines, I see three-quarters of the audience blanch—Mary Beth has an impossibly high voice, one that can make your head explode if you’re not prepared. I watch, as the assembled parents simultaneously lift their cocktail glasses and take a solid swig. But—surprise—Mary Beth has planned a special arrangement of “Down in the Valley”—one that includes cartwheels—twenty-four cartwheels—we count them. When she reaches the end, she modulates to an even higher key—down in the valley, the valley so low—raises her grass-stained hands, and sings the final verse. Wow.

“Thank you, Mary Beth!” says my sister. “A true highlight.”

“Next up, my sister, Robin, performing a medley of the two songs she knows.” I smile and stand in the middle of the courtyard with my flute. Poise. I play “When Sunny Gets Blue”—a tune I found in my dad’s fake-book—then segue into a vocal performance of “This Land is Your Land” which I can sing while twirling the flute. My range isn’t as impressive as Mary Beth’s, and there are no flames shooting out of my flute tailpiece, but I get by.

Some of the other girls perform splits and back-bends. One of them plays the violin. Alyce Amery recites poetry. Mary Helen does an interpretive dance with scarves.

We are fearless. We believe in our beauty, our talent, our intelligence, our poise.

We change into Sunday school dresses—our version of evening gowns—for the final round of the pageant. For music to accompany our final walk down the runway, we hum “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

The tension builds. Randy has decided in advance to eliminate the runners-up. No finalists. She will select the winner and that will be that.

We hold hands and glance nervously at each other, just like the real Miss America contestants. Who will win? I will win. I know I will win, but when I look at the other girls, I see the same spark of determination in their eyes and begin to doubt myself. Maybe the flute twirling wasn’t such a great idea. We can’t all win. This isn’t as much fun as I thought it would be.

Randy asks for a drum roll. The parents in the audience put down their drinks and pound their thighs.

“And the winner is . . . ”

Drum roll . . .

Randy glances at the paper crown, bouquet of dandelions, and the crepe paper Miss Chatham Village sash she has stashed on a table next to her.

“And the winner is . . . ”

Drum roll . . .

“Me!”

Randy crowns herself. I stand with the other girls onstage, our mouths hanging open in disbelief, as Randy adjusts the crown, pulls the sash over her head, grabs the bouquet, and sashays—with tremendous poise—down the runway, pausing to wave at our parents and the imaginary press corps lining both sides of the aisle.

Halfway between rage and devastation, we begin to howl. Our parents sit there laughing, which does not make things better, not one bit.

“No fair!” we shout. “No fair!”

“Fair!” says Randy. “You made me the judge and I picked me.”

“You didn’t wear a swimsuit or an evening gown. You didn’t even have a talent presentation.”

“Yep,” says Randy. “I was just myself. And I won.”

“You can’t do that!” Mary Beth says.

“Yes I can. You know why? Because I’m the judge. I decide. You want to win, you have to be the judge! Any nitwit knows that.” Randy, my worm-eating devil sister, spins around and takes another turn on the catwalk. Our parents stand and cheer. The other girls and I—feeling very much like the Chatham Village idiots—stomp out of the courtyard and go to my house to change clothes. Losers! We are worse than Miss Michigan—we’re not even runners-up. One by one, we slam the screen door in protest. I look out and see Randy, still wearing her crown, signing autographs for the adults. I suppose this time next week she’ll be riding on a float in a parade on Grant Street.

*****

You want to win, you have to be the judge.

Randy had a point. It will take me decades to figure out that my little sister, age seven, was wise beyond her years—smart enough to be the judge instead of the contestant; rebellious enough to make the rules instead of following them; quick enough to crown herself instead of waiting for someone else to do it for her; cunning enough to win the top prize without stuffing herself into a swimsuit or Sunday school dress. You want the tiara? Make it yourself.

And what about Grandma’s favorite quality— poise? Randy comes by that naturally, I’d say. No one can strut a runway like my sister.

*****

Randy Rawsthorne Cinski is now the owner of Randita’s, an organic vegan café located in Pittsburgh. She makes great food and tells good stories. And if you’re lucky, she might even be wearing her crown.

Robin Meloy Goldsby is a Steinway Artist. She is the author of Piano Girl; Waltz of the Asparagus People: The Further Adventures of Piano Girl; and Rhythm: A Novel.

New: Manhattan Road Trip, a collection of short stories about (what else?) musicians.

Sign up here to receive Robin’s monthly newsletter. A new essay every month!

Robin Meloy Goldsby is the author of Piano Girl; Waltz of the Asparagus People; Rhythm; and Manhattan Road Trip. She has appeared on National Public Radio’s All Things Considered and Piano Jazz with Marian McPartland. Robin is a Grammy-nominated lyricist and has received a Publishers Weekly Starred Review for her book, Piano Girl.. A Steinway Artist and cultural ambassador with artistic ties to both Europe and the USA, Robin has presented her reading/concert program for numerous women's organizations and embassies worldwide.

Great story about poise, determination and one fearless little girl. She certainly didn’t take guff from anyone and made up her own rules. She was old beyond her years, to the chagrin of all others assembles. Your stories are always vivid with detail and take us right to place and time. They are a delight to read.

What a coincidence! First story I read and it takes place in Chatham Village, where I moved in 2013. CV has grown long of tooth but the longtime residents are happy to tell stories of what it was like when it was full of families with children. This first person adventure was just a hoot to read. Great writing, captures the spirit of Randy perfectly.

Wow, another CV resident on Retrospect? What are the odds? We were at 614 Pennridge when this story took place, and later moved next door to 612. I often visit one of my best friends who lives on Olympia.

Thanks for reading—maybe you can organize a beauty contest sometime this summer. The Upper Court is perfect for cartwheels. xoxo RMG

I thoroughly enjoyed this story, and was caught between admiration for your sister and sympathy for you and your friends. There are so many great details, like the special arrangement of Down in the Valley—”with cartwheels!” It’s also a lovely tribute to your sister and an insightful lesson about our unfounded yet persistent expectation that life will be fair.