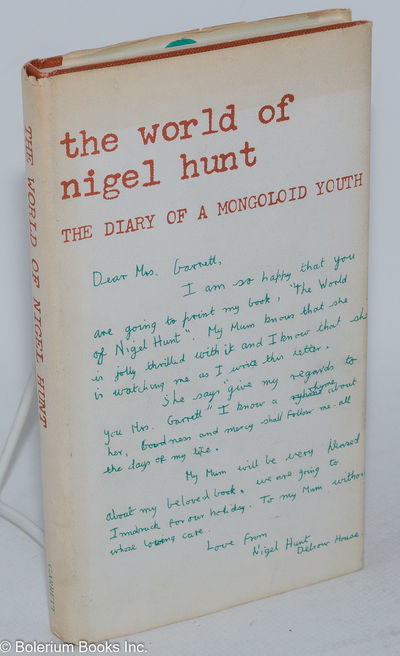

A book that truly grabbed my attention, expanded my imagination, and overturned some of my prejudices was a very slim, orange-colored volume titled, “The World of Nigel Hunt/Diary of a Mongoloid Youth. ” I found it because it was listed as supplementary reading for a course I was taking in 1971.

Nigel understood that what he was doing in recounting his everyday activities and observations was subverting most people’s understanding of what was possible for a person with his condition. He mentioned this frequently throughout the narrative—though he never used a verb such as subvert.

The author (Nigel Hunt, age 17) explains in his brief narrative that he not only thought up the contents of the book but seems equally proud to proclaim that he also typed it. And why not? In 1967, when this book was published in the United Kingdom, no one in that country, in the USA, or anywhere else had it in their playbook that a person with Down Syndrome could possibly learn to type! Leave aside for the moment the fantastical notion that he or she could be typing up material that he himself had conceptualized, sequenced, and laid out on the page.

A brief detour related to lexicon: I am referring to Mr. Hunt as a person with Down Syndrome, but you will note that in his book title, he refers to himself as a Mongoloid. The latter is also the term my family was given for my sister’s condition, when she was born in 1965. (I was in high school at the time.)

The term “Down Syndrome” was not widely used until the 1970s. Repugnant as it may seem now, “mongoloid” was itself introduced as a kinder, softer replacement for the harsher term, “Mongoloid idiot,” which had been the more prevalent term used for this condition by doctors and other professionals in earlier generations.

The book came just in time for me. I was a mostly cerebral kid at age 20. I could tear up at a movie (say, The Sound of Music) but neither jubilation nor grief nor anger visited me much as I studied my course materials or attended classes. That is, until I was taking a course in child development with a bunch of graduate students in 1971. It was my final year of college. I had returned from a year away from campus (forced to withdraw due to participation in disruptive political activities in 1970), I had begun working at a childcare center, and for the first time found I was interested in choosing courses that might have relevance to what I was doing in the nonacademic part of my life.

It may sound utopian, but when I entered Harvard in 1967, I thought about higher education as a place to further refine and extend my intellect and generally become a more knowledgeable and well-rounded person. I had parents who took intellectual development seriously, and they had never pushed us to think about future professional choices when we were heading off to college. From early childhood, learning was highly prized in our family, and I pursued it (along with my siblings) for its own intrinsic merits. When I chose Harvard, it was not because it was a pathway to a career or a good place for what people in later generations would call “networking opportunities.” When I chose my college, my classes and eventually my major (history and literature of 19th and 20th century England and France), I had no thoughts about where they might lead. I just wanted to become as well educated as I could, and I wanted to study subjects that were of interest to me. But now, for the first time, coming back from being away, I was taking a class with “real-world” implications.

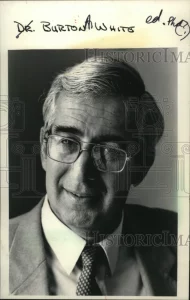

There I was, sitting in a seminar on Preschool Child Development, taught by the eminent (and soon to be quite famous) Dr. Burton White, Director of a research study called the Harvard Preschool Project. The findings of this study, which he was sharing in class as they emerged, would lead him to write a best-selling book, The First Three Years of Life.

I’m sitting there, myself and about 12 to 15 graduate students—more women than men, which was the converse of every single class I had taken up to that point at Harvard. And one of the women, responding to some research the professor was discussing, said, “What you’re saying may apply to most children. But it certainly doesn’t apply to all. I’m thinking, for example, of mongoloid children. They can’t even learn to hold a spoon or a fork and feed themselves! And I know, because…” She went on to detail her bonafides. I can no longer recall if her knowledge was based on knowing someone personally, or perhaps she had volunteered at a state school or institution. In any case, she expressed what to me seemed like an alarming level of certainty in categorizing a whole class of human beings and relegating them, as she had, to a life of total dependency and little quality. And suddenly, I felt my heart and my body gripped by anger, riveted by the unfairness of what she was declaring.

I could not respond in class; I did not have the tools to verbalize any of what I was thinking or feeling. Perhaps I would have felt comfortable attempting to do so among a group of undergraduates. But here at the Harvard University Graduate School of Education, where I had sought and received special permission to “cross-register” and count the class towards my own credit load, and where they all appeared to be adults in their 20s to 30s, while I was just a kid, I could not speak up.

I knew my sister Laurel, aged five, could hold a fork and a spoon and feed herself. I knew that she could pump herself up on a swing. I knew that Laurel had a working vocabulary, even if it was considerably less extensive than that of a more typical peer of the same age. Laurel’s foster mother had told Mom that she banned Laurel from using the expression, “I can’t.” “Yes you can, Laurel.” That, she said, was her mantra. That’s how she said she had taught Laurel to do so many things for herself, including sitting at the table and eating and using her utensils and her napkin. There was no way to verify her methods or her words of guidance, but the proof was in the pudding: I had seen my sister feed herself.

Why was the world full of people who were ready to make over-generalized statements like this? Bad enough if it happened in the world in general, but even in a graduate school of education? I was in tears. I was full of rage. I was in righteous solidarity with my sister, who was 900 miles away in Indiana. I had only gotten to spend time with for a few hours here and a few hours there, since our parents had made the decision to put her in foster care after she was born, and then I left for college when she was only two. But I knew her well enough. My attachment was sufficient that I burned with grief and indignation on her behalf, and on behalf of all families who were doing their best to help children like her develop and learn and grow.

Right around that time, I was looking at the supplementary reading list for our class, on the bottom of Dr. Burton White’s syllabus. And I saw the title. The autobiography of Nigel Hunt: Diary of a Mongoloid Youth. Author, Nigel Hunt. Was this possible? Right in our own syllabus: proof that someone labeled as “mongoloid” could do a whole lot better than just hold a spoon or a fork?

I got the book off the reserve shelf of the library and read the whole volume in about an hour. It was just what I needed to calm myself down.

My copy of the book—which I would order many years later to reread and to keep as my own and eyed fondly and with gratitude over the years—is not in the location where I am writing this piece. Therefore I cannot quote from the book or even summarize it with great confidence. But I can relate that Nigel spent the narrative recounting his own daily activities such as his routines at home, doing errands with his mother (who gave up working after he was born, in order to devote herself to supporting his learning and development), and traveling with his parents. He described other people he met and other places they visited.

Nigel understood that what he was doing in recounting his everyday activities and observations was subverting most people’s understanding of what was possible for a person with his condition. He mentioned this frequently throughout the narrative—though he never used a verb such as subvert. So many decades later, I remain impressed that someone only 17 years old had such a depth of insight into the way the world looked at people like himself.

Another thread that was prevalent throughout was his sense of humor. He seemed to be amused that he was going to challenge so many people’s expectations. He was not angry or self-righteous or hurt. To the contrary, his story is full of a breezy optimism. Not necessarily optimism about the future of people with Down Syndrome (or people more generally with disabilities). He was optimistic about his own expectation of living a happy and meaningful life. I have made some efforts to discover more about his later life on the Internet, but without finding a thing. If anyone can search more successfully than I, I hope they will add a comment and let us all know about the trajectory of the author’s life.

Regardless of what became of Nigel Hunt as he grew into manhood, his book was a massive achievement that needs to be honored. Even though I knew that my sister could hold a spoon or a fork, I did not realize that she had the potential to interact with the world in as full and literate a way as Nigel showed me. With his book, he upended and expanded my understanding. Never, after reading that book would I underestimate what my sister could do, nor what others labeled with all kinds of congenital or acquired conditions could do.

I was heavily inspired and influenced by another autobiography from the same era that I read a few years earlier than this one—The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Happily, the world has continued to celebrate that important book and made sure people have read it for several generations now. For families of people with Down Syndrome and other disabilities, and even for people who believe in a more inclusive world, I would like to see The World of Nigel Hunt occupy that same kind of niche.

Dale Borman Fink retired in 2020 from Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, MA, where he taught courses related to research methods, early childhood education, special education, and children’s literature. Prior to that he was involved in childcare, after-school care, and support for the families of children with disabilities. Among his books are Making a Place for Kids with Disabilities (2000) Control the Climate, Not the Children: Discipline in School Age Care (1995), and a children’s book, Mr. Silver and Mrs. Gold (1980). In 2018, he edited a volume of his father's recollections, called SHOPKEEPER'S SON.

Thanx Dale for introducing us to Nigel and to your sister Laurel..

Reading your story I thought of my nephew Michael who is an autistic.

After many difficult years he is now living in a wonderful county-run group home where he’s bonded with his housemate Scott.

At 31 Michael has become a happy and functional young man. Sadly my sister who succumbed to MS almost 10 years ago did not live to see him now. I haven’t written about Michael but you’ve inspired me to try.

Thank you, Dale!