Maybe I’d breathed a little too much tear gas during anti-war demonstrations on the UC Berkeley campus—or maybe it had to do with the direction my grades were headed—but after one year I was convinced I wasn’t ready to be a full-time college student. I needed time to figure out what I wanted to do with my life. I learned I could withdraw from the university and return after a year. After filing the necessary paperwork, I informed my parents. They were not overjoyed to hear the news.

I found myself sitting next to women my age, or not much older, who were military wives. They came from the Midwest, the South and back East.....Their husbands were off fighting in Vietnam while these young wives held down a job, kept house, took care of the car, called the refrigerator repairman, paid the bills, and tried to stay sane.

“Once a dropout, always a dropout,” said my father, the teacher. “If you’re not going to school—you have to find a job.” There would be no break, no time to contemplate my future. He made that clear.

I started my search for employment by circling ads in the newspaper for administrative assistants or entry-level clerks with “good people skills.” No college degree required.

Getting a job meant financial independence—my primary goal. As soon as I found work and got a regular paycheck, I planned to move out of my parents’ house. Most of my friends were already living away from home. They didn’t have to whisper when their boyfriends called or suffer through the third degree after a date. They didn’t have to listen to their parents argue. I was on the runway, ready for take-off. All I needed was a job.

I believed I could find gainful employment despite my lack of typing skills—or any other skills, for that matter. I knew I couldn’t pass a typing test; I’d never learned to touch type even though I took the silly class in high school. Typing presented a hurdle I couldn’t get over, and most jobs required so many words a minute with no peeking.

What I did have was a familiarity with three foreign languages, the belief that someone would hire me, and some cute interview outfits.

Did I have a résumé? No.

Did I have any previous work experience? Not unless you count occasional babysitting and teaching Sunday school.

Did I have a plan? Yes. I would:

- find companies eager to hire an eighteen-year-old inexperienced high school graduate with no marketable skills

- fill out their applications; and

- land a job

I pulled on my pantyhose, put on some eyeliner, and went job hunting.

I walked up and down the hills of San Francisco, into the high-ceilinged lobbies of shipping companies and offices I thought might have an international business angle. I filled out the applications and failed each typing test. After yet another promise from an unconvincing receptionist that she would keep my name on file, I consoled myself with rice pudding and coffee at the closest lunch counter. I was beginning to lose faith in my plan.

Five weeks later, thanks to a timely word from a friend of my sister, I got the inside track for a job as a telephone operator with Ma Bell—the phone company. I aced the entrance test (no typing required), filled out the application, went home, and waited for a phone call. I didn’t wait long to hear the news: I would begin my new job as a long-distance operator in downtown San Francisco by the end of the year.

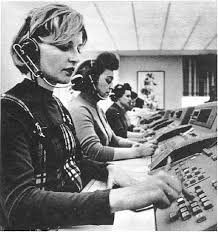

My building was in the financial district. The operators sat in front of consoles, two by two, in long rows. Trainees went into a small glassed-in room just off the main floor. We could hear the low voices all around us. “GoodmorningmayIhelpyou?”

All the new hires went through several days of training and role playing. We were given a script to follow. We had to learn a variety of procedures that involved multitasking, before multitasking was a thing. I got freaked out the first day, worried that I would never learn the right way to do everything at the same speed as the veterans out on the floor.

We were not encouraged to improvise or inject our personalities into our calls. If it wasn’t in the script, we didn’t say it. (With one exception: when our union, the Communication Workers of America, called for a walkout, we had to come up with something to say. “I’m sorry sir, but the operators are going on strike. Can you please try your call again later?”)

After a couple of paychecks, I moved into my sister’s apartment in Berkeley. We shared the rent and took turns cooking. I commuted to the city by bus five days a week in my miniskirts and platform shoes or maxi skirts and boots, accessorized with dangling bead earrings I’d made myself; not quite a full-fledged hippie, but close. I stopped for a danish on the way to work almost every day, snuck in quick shopping trips at lunch, and had a slice of cafeteria cherry pie on my afternoon break. I usually fell asleep on the bus ride home.

I found myself sitting next to women my age, or not much older, who were military wives. They came from the Midwest, the South and back East. As a Bay Area native, I felt like the odd one out. Their husbands were off fighting in Vietnam while these young wives held down a job, kept house, took care of the car, called the refrigerator repairman, paid the bills, and tried to stay sane. I learned about their struggles to be competent—but not too competent— so the men wouldn’t suspect their wives were becoming totally self-sufficient.

Patty from Michigan came to work wearing knee-length skirts, heels, and pearls, with her hair in a French twist. Patty’s husband had been gone for a year, and she was used to being in charge of her life. She was brisk about her work and confident in her manner. Once we got to be friends, she shared some of her “how to make a man happy” tips. I blushed; she didn’t.

Before a brief R&R in Hawaii with her husband, the Army gave Patty her orders: “No trouble, no arguments, no nagging. You know what your job is.” Shortly after she returned to work, she got a letter from her husband: he wanted a divorce. We rallied around her as she fought back her tears, clutching the letter in her fist. She’d gone so far to see him and tried so hard to follow instructions, but they got into a fight about changing the oil in the car or some damn thing, and that set him off. After a couple of weeks he cooled down and apologized.

I had been paired in training with Trina, who came from a small town in Texas. We were the same age. She was quiet and shy, and wore skirts and sweater sets or simple dresses to work. Her wicked sense of humor surprised me. Before her husband shipped out, he gave her strict instructions: she could not go out at night, she was not to associate with any hippies, and she must sleep with a gun under her pillow for protection. Trina broke two of his rules with me as an accomplice: one night after work she went to the movies—and the hippie friend she wasn’t supposed to have (me) went along with her. I’d also accepted her offer to stay over after the movie, but I wished she’d told me about the gun before I said yes. As it was, I didn’t get much sleep.

I told Trina I thought it was unusual to get married so young. None of my friends were even thinking about it. I couldn’t imagine being married at our age. Why would you, when you could just live together? She said the girls in her senior class posed for their yearbook pictures with their left hands touching their right shoulders so their engagement rings would show. Then she pulled out a drawer and showed me the baby clothes—for when she and her husband started a family. I looked at the little sweaters and booties and considered how different our lives were. Trina knew what her future looked like: Texas, kids, marriage, keeping house. Her life seemed set out in front of her like a long stretch of blacktop.

I still had no idea what my life would look like. Would I go back to school? Or would I keep eating too many baked goods while stuck in a dead-end job, drifting along through life, continuing to disappoint my father? Was the answer really blowin’ in the wind? Where was my plan? I’m not saying I envied them—married already, with big responsibilities—but I felt nowhere near as grown-up as my co-workers. I hadn’t expected to feel that way. I’d been to college after all. I was smart, wasn’t I? Why didn’t I feel more like an adult?

I’d never expected to get to know people like Patty and Trina and the others: they came from small conservative communities, had strong religious beliefs, and were shocked to find themselves living in the same city as the Haight-Ashbury, home of the fizzled Summer of Love. I’m sure I was a curiosity to them also. A Jewish girl. From Berkeley. Not married or engaged at nineteen, on the Pill, free to come and go with no one telling me how to behave, dreaming of bigger things, making my own plans. Or not. It felt like freedom to me. But I’d been living in the Berkeley bubble. Hippies were cool, straights were the enemy. The war in Vietnam was wrong and no one should have to be there. Hell no, we won’t go. Make Love Not War.

Still, even guys in Berkeley were required to register for the draft when they turned eighteen. There was a lottery every year, and each young man got a draft number based on his date of birth. The day the numbers were published in the newspaper, I ran my finger down the columns until I found my boyfriend’s number. It was high—356. I was relieved to know where he stood, even though he had a college deferment and wasn’t going to be drafted. I didn’t mention my boyfriend’s draft number at work that day, and no one asked me about it. I was aware that Trina and Patty and others had husbands who were risking their lives in a war I had marched in the streets to protest. I was against the war, not against those men. I knew their names and where they were from. Their wives were my friends.

This was a gap year for me, a time away from school, working to support myself and feeling independent. I thought it would be a break from my education, but I actually learned more than I’d bargained for, spending my days alongside women who were dealing with real life and real problems. You wouldn’t have called my friends liberated, but you would have called them women. And despite my show of independence, next to them I still felt like a girl.

I don’t even remember what I learned in my Sociology of Women class, but by talking to my work friends I came to see how women can adapt to difficult roles with strength, courage and dignity. What they knew didn’t come from reading a textbook. My friends’ lives were real, much more real than mine. They had jumped into the adult worlds of work and family life, and didn’t waver from that path—at least not when I knew them, when we were all young. From them I learned that marriage means commitment. The vows they took weren’t always easy to stand by, but they did it. Marriage seemed less like a someday possibility and more like something I wanted for myself one day.

Before I became friendly with the women at work, Vietnam seemed a world away. The issues were black and white. War was wrong and we were right. But as I got to know my friends better, something changed. I still didn’t support the war, but I did support my friends as they took care of business, treading lightly with their absent husbands to keep the peace at home, wise beyond their years.

.

Risa, this is such a great story! I love your job qualifications: 3 foreign languages, a belief that someone would hire you, and some cute interview outfits. That sounds like me jobhunting AFTER college, so okay I had an A.B. too, for whatever that was worth. And your work attire sounds familiar too: miniskirts and platform shoes or maxi skirts and boots. Of course we wouldn’t have dreamed of wearing pants in those days.

What is so different from my experience, and so fascinating to me, is the women you got to know through your job, what you learned from them, and the impact the Vietnam war had on them. Thank you for this totally different perspective on the war.

Thank you so much, Suzy. It was an interesting time to be working alongside those brave women.

You give us a different, unexpected way into this prompt, Risa. We learn much about the women left behind by the men going off the Vietnam and a bit about the men they married and what is expected. You don’t judge them and they (and we) become their friends. It does point up the different expectations, levels of education and, perhaps, faith-based communities that in so many ways have come to dominate much of the culture wars and perhaps even the current on-going divide in our culture. If we could all get to know one another on a personal level, as you did, I suspect there would be much less division in our landscape today.

Thanks for these comments, Betsy. People didn’t really focus on how hard it was on the wives who were left behind to manage, but not manage too well.

Risa, this story blew me away. What started out as a light piece about dropping out of college and finding a job with no qualifications — which I confess puzzled me about its relevance to the prompt — then plunged us into an unfamiliar world where lives and marriages were on the line. I felt for you as you empathized with these women, and I love your wry insights about what you discovered and learned. Brava!

It also makes me wish I’d taken a gap year like yours — a topic that might find its way into a prompt one day.

Thanks, John. This was a mind blowing experience for me…glad you enjoyed it!