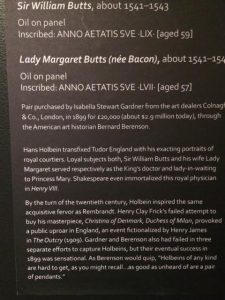

Lady Margaret Butts by Hans Holbein the Younger at the Isabella Stuart Gardner Museum, Boston

I took a course on Northern Renaissance painting with Professor Ludovico Borgo in my last semester at Brandeis. For our final project, we had to write a research paper on a painting from that era that we could visit in person. We had to analyze the provenance of the work, history of restorations, and research other scholarly information. It was much more than just a discussion of the surface qualities of the painting itself. This required real determination and I was truly jazzed about the assignment.

As a life-long fan-girl of Tudor England, I chose to write about either of two Holbeins at the Gardner Museum in Boston. At the time, the Gardner was a beautiful, but sleepy institution on the Fenway, close to the Museum of Fine Arts, with an incomparable collection of just about anything that Mrs. Gardner had chosen to assemble on her many trips to Europe and bring to the Italian palazzo she built in Boston. Similar to the Frick in New York City, this was also once a private home and collection. However, she had always planned to open it to the public.

Hans Holbein the Younger was the court painter to Henry VIII. Mrs. Gardner owned portraits of Dr. William Butts, Henry’s court physician, and his wife Margaret Bacon, Lady Butts. They flanked one of the entrances to the Dutch room, home to some of the most extraordinary and valuable paintings in the museum.

I began my research at the Brandeis library. That got me only so far. Finally, I had to go into Boston. I called the Gardner and spoke with their curator. It was a Friday and a week before my paper was due. She was annoyed. “Oh no! Not ANOTHER one of you Brandeis students!” I assured her that I would be the last to bother her, as the paper was due soon. She let me come over that afternoon.

I was 21 years old. She wasn’t much older. No one else was around. I was polite. I told her my topic and how excited I was to be investigating the subject, as I was really a theater major. I took art history for fun. She perked up. Did I know Gil Schwartz? He was a recent Brandeis theater grad who was working at an improv club in Boston. She’d met him at a party the previous weekend. (Gil was a very handsome, whip-smart guy. He went on to a successful career at CBS, retiring not too long ago as VP of Communications. He wrote smart, funny business books under the pen name Stanley Bing. I googled him recently and was stunned to see that he had dropped dead of a heart attack shortly after retiring. He was a year ahead of me. We had been in several shows together.) When I assured her that we were friends, the mood in the room changed considerably and I was given access to EVERYTHING!

I spent hours reading Bernard Berenson’s letters to Mrs. Jack (as she was informally known), detailing when he first found the paintings in England, what kind of shape they were in, advising her on how much she should pay for them, how quickly she should buy them. These were the REAL letters (I wore white gloves and the letters were in a protective sleeve); not microfilm or reproductions, but the REAL letters, as I sat, reading in a Gothic alcove of this incredible space. I was transfixed. It was a “you are there” moment. It gave me so much of the information I sought.

After soaking all this up (and taking copious notes), I gratefully returned the folders to the curator and went up to the solitude of the magnificent gallery. I sat, cross-legged on the floor and contemplated the two stern faces in the paintings. Ultimately, I decided to write about Lady Butts (painted about 1541-1543) because she had had less restoration done through the years. The room was all mine, and is forever linked to that special day. More than 46 years later, I have a personal affinity with that room.

So I was stunned when the news broke that two men, dressed like police men, had broken into the poorly protected jewel of a museum in the early hours of March 18, 1990 and stolen incredibly valuable works of art, including three works from that room: a Vermeer – “The Concert” (and there are SO few in the entire world) and two Rembrandts, including the only known seascape he ever painted: “Storm on the Sea of Galilee”. I had a 10 month old baby at the time, but I cried unconsolably myself. It was unthinkable. I took the theft personally. That was MY room, MY space that had been violated.

30 years later, the works have never been recovered. I don’t believe they ever will be, as they are fragile and wherever they were hidden, (they were slashed right out of their frames) they most likely have not been in proper climate-controlled conditions, and have deteriorated beyond repair. It is also possible that anyone with any knowledge of the theft has died by now.

My voice trembles and I can barely keep it together when I take friends through the museum and show them my room. It reminds me of a transcendent afternoon I spent there in May, 1974.

Retired from software sales long ago, two grown children. Theater major in college. Singer still, arts lover, involved in art museums locally (Greater Boston area). Originally from Detroit area.

A well-drawn depiction of a day that was special to you. Thanks for sharing!

Gina and I lived in Boston (well, Quincy) for six years while she got he PhD at UMB. Only went to the Gardner once, but we were impressed. Thieves are terrible; ART thieves are worse because they steal from all of us.

Thank you, Dave. I agree, art thieves are the worst as they deprive the public of seeing these great treasures, perhaps ever again.

This is a lovely story, Betsy, but the art theft makes it tragic as well. I will never understand the motivation to steal art that cannot be sold for profit because it is too famous.

Thank you, Laurie. I agree, as I think back to that special day, and how it all changed after the theft. I can never look at that gallery the same way now. Like you, I just don’t understand the motivation of people who would do something like that.

Art thieves aren’t particularly smart (contrary to romanticized characters in film)…imagine their chagrin when they realize they can’t monetize their valuable heist. Your story was heartbreaking but also so touching, Betsy…a transcendent afternoon indeed!

Thank you, Barb. That memory came back to me during my 40th college reunion when we were asked by the yearbook committee to write about our “best day ever during college”. I didn’t answer for the yearbook; I really had to think about it (this was 6 1/2 year ago, but realized that day at the Gardner was it (though it didn’t happen on-campus).

I agree, what’s the point of stealing something that can never be re-sold or shown anywhere? Just burns me to think about it.

A bittersweet memory, Betsy, of your “room.” Love Holbein and each time I’d visit NYC I’d go to the Frick (best kept museum secret there). My heart hurts every time I learn about an art theft, so I can relate.

The Frick is also a special place. I first went there alone when in NYC for a wedding some years ago and came face to face (up close) with many well-known paintings including the Thomas More by Holbein (arguably better known than either of the Buttses).

More recently, the Gardner added a huge wing, designed by Renzo Piano, which added space for a cafe, special exhibit space, a “living room” where museum-goers may rest and look at art books, a concert venue, gift shop, and conservation space, so, even though it had to go to court to break Mrs. Gardner’s will (which said nothing could be changed from the way she left it), it is a much more functional museum.

Betsy; this reads like an art caper film!

So sorry for the desecration of your special “room”!

Thank you, Dana.

Betsy, I love this description of your final project, and how you went about completing it. Talking to the curator, who started out icy, but thawed upon the discovery of a mutual friend; wearing white gloves to read the original letters; and finally sitting on the gallery floor to contemplate the paintings. I bet you wrote a fabulous paper. How sad that 16 years later, three paintings were stolen from that gallery. I expected you to say that one of them was “your” painting, but even though it wasn’t, that was still “your” gallery. I understand taking it so personally, especially being the art lover that you are.

Every moment of that afternoon got better and I was proud of the paper I wrote, though I remember only receiving a B+. I think the professor thought I was a Fine Arts major so graded me on a higher scale than he would someone who took the course for fun, as he seemed shocked at Commencement when he realized my degree was in Theater.

It is true that the Holbeins are still on view in the gallery, but it feels like that sacred space has been violated. Very sad.

Those of us who have been attached to Boston for many years with any sense of art know and adore the Gardner. And, of course, know of the infamous theft that took place years ago. So your special memory of a special day at the Gardner — when everything was still “intact” — really resonates with me. (Indeed, I wish I had better memories of my visits to it in college, when I was generally rushing through it to see the “required” paintings for my art history course.)

Your description of your connection with the Gardner is so compelling and so well explains the strong — and very sad — reaction you have, even now, when you visit “your” room there. Very moving. (No pun intended.)

Thank you, John. It remains a very special place (in fact, they have launched an effort – room by room – to clean and restore all the magnificent work, so it isn’t nearly as dusty as it used to be, which is why I got the up-close shot of Lady Butts; she had been moved to a different gallery when her normal spot was being cleaned). Still worth a visit after the pandemic.