Although our two older children had taken French since elementary school, when we needed to rebook our arrangements for a Paris hotel because their younger sister had come down with chicken pox, they were the ones who chickened out. They refused to talk to the hotel concierge to explain our need to arrive a few days later than planned, claiming they never learned how to speak French in French class. While this was probably true, it left my husband, who could get by in Spanish and Hebrew, to have the following conversation with the hotel:

We knew from past experience that we would struggle in Paris unless our kids helped, which they refused to do.

Âllo Oui, said the person who answered the hotel phone.

Âllo Oui, said my husband.

Âllo Oui, replied the hotel.

Âllo Oui, answered my husband.

This went back and forth for a while until one of our kids said, “Dad, that just means hello yes, or what do you want?” Nevertheless, my husband persisted and eventually was able to get across the necessary information.

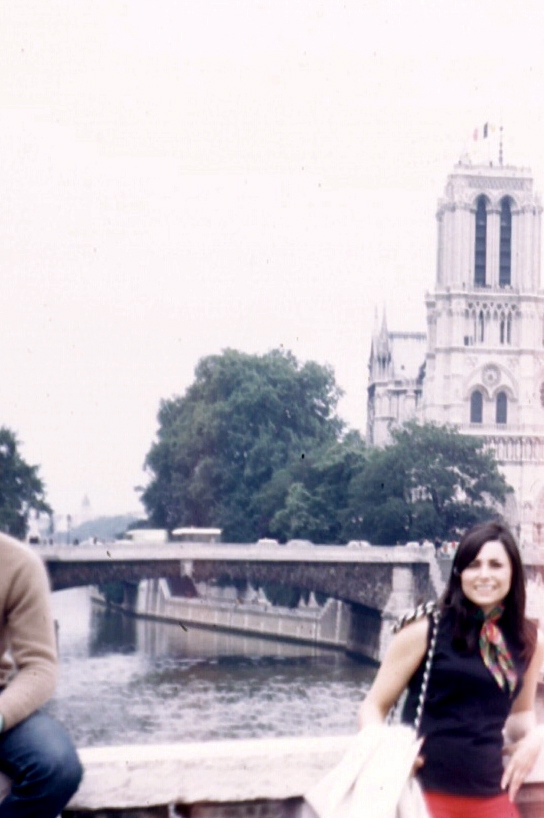

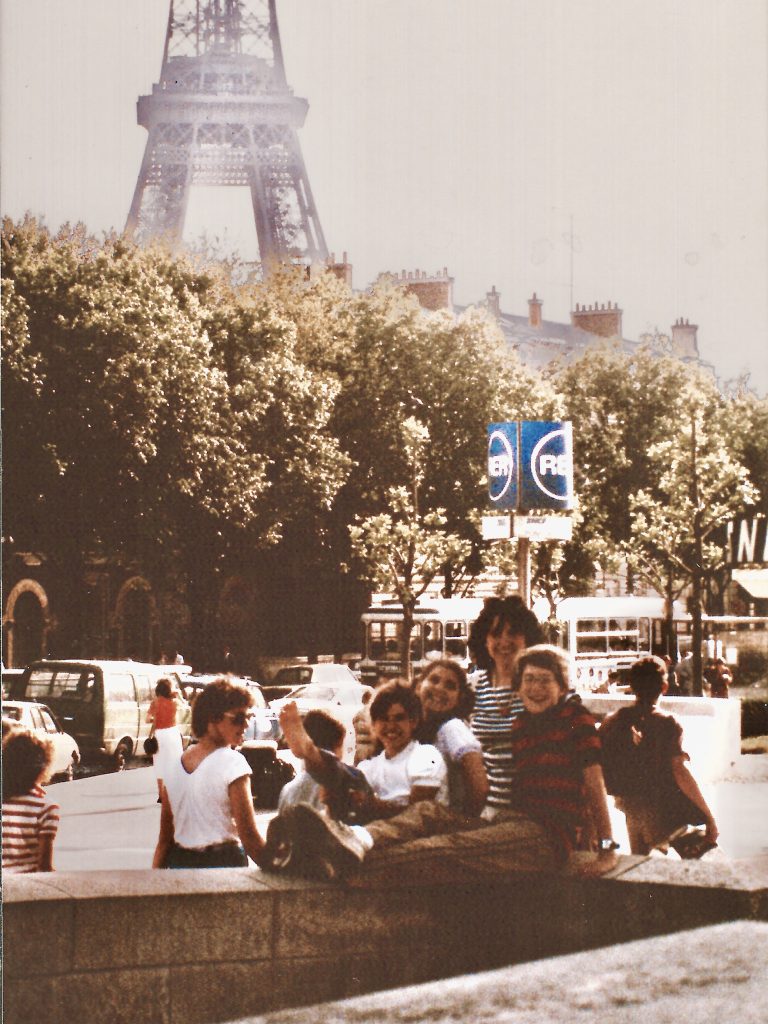

We knew from past experience that we would struggle in Paris unless our kids helped, which they refused to do. Having been there in 1969, when no one would speak to us in English to help us pay the correct amount for a bus or find a place to fix the broken heel of my shoe, we had hoped that by 1984 our ability to communicate would have improved. Using our trusty English to French dictionary didn’t help much, however, as whatever we tried to say was lost in pronunciation or translation.

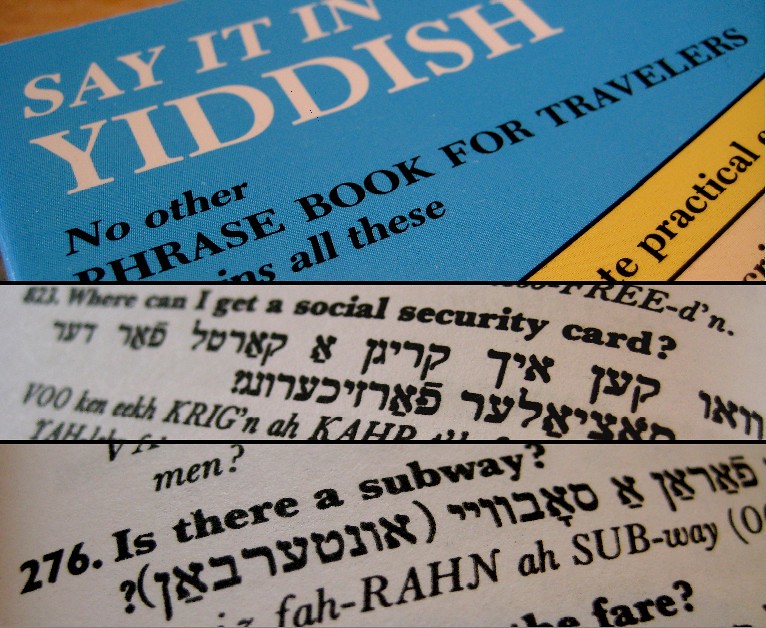

Of course, I knew growing up about words being lost in translation. My grandparents emigrated here from Lithuania and the meaning of many of their Yiddish words were definitely changed when they became part of the American lexicon. Some examples include:

Kvetch, the Yiddish term for “to complain” or “to whine.” But when my parents told me to “stop kvetching,” it had a more commanding and negative connotation. The message was to cease and desist from making an unreasonable complaint immediately.

Mensch has adopted the meaning of someone who is a “stand-up guy” or a person with integrity. But in my childhood, a mensch was a good person in a more religious, moral, or righteous sense.

In English, the verb plotz describes someone who is bursting with intensity or emotion, as in laughing until you cry at a comedy routine. When my parents used the word, it often meant trying to control yourself if you had good gossip to share, as in, “I’m plotzing to tell you this.”

Other words I often heard growing up that are less commonly used in English include:

Shande, a scandal, embarrassment, or something extremely shameful.

Chutzpah, having extreme self-confidence or a lot of nerve.

Schmatte, literally a rag, but more often used to describe old or out of style clothing. My mother would tell me, “Are you wearing that schmatte on a date?”

Yiddish is a dying language (although some of my friends study it and it is spoken in very Orthodox Jewish communities). There is something sad about these words losing some of the richness and nuance of their original meanings. I do have to laugh, however, when my Korean-born son-in-law sprinkles Yiddish words into our conversations. Or when he tells us not to put the chicken before the cart. I’m sure there are many words from the language he spoke until age five that are lost in translation, even when he tries to explain them to us.

I can’t leave this topic without sharing a few laughs on translations into English from other languages (my apologies for not remembering where I found these):

• Cocktail lounge, Norway: “Ladies are Requested Not to have Children in the Bar”

• Hotel in Acapulco: “The Manager has Personally Passed All the Water Served Here”

• Tokyo hotel’s rules and regulations: “Guests are requested NOT to smoke or do other disgusting behaviors in bed.”

• Hotel lobby, Bucharest: “The lift is being fixed for the next day. During that time, we regret that you will be unbearable.

• In Nairobi restaurant: “Customers who find our waitresses rude ought to see the manager.”

• On the menu of a Swiss restaurant: “Our wines leave you nothing to hope for.”

• Hotel in Japan: “You are invited to take advantage of the chambermaid.”

• Outside Paris dress shop: “Dresses for street walking.”

• In a Rhodes tailor shop: “Order your summers suit. Because is big rush we will execute customers in strict rotation.”

• Hotel in Zurich: “Because of the impropriety of entertaining guests of the opposite sex in the bedroom, is it suggested that the lobby be used for this purpose.”

• Airline ticket office, Copenhagen: “We take your bags and send them in all directions.”

• In a Bangkok dry cleaner’s: “Drop your trousers here for best results.”

• Detour sign in Kyushu, Japan: “Stop: Drive Sideways.”

• Japanese hotel room: “Please to bathe inside the tub.”

• Instructions on a Korean flight: “Upon arrival at Kimpo and Kimahie Airport, please wear your clothes.”

• Athens hotel: “Visitors are expected to complain at the office between the hours of 9 and 11 A.M. daily.”

I hope you plotzed reading these.

Boomer. Educator. Advocate. Eclectic topics: grandkids, special needs, values, aging, loss, & whatever. Author: Terribly Strange and Wonderfully Real.

With my long-ago high school French, I had a similar situation on our first trip to Paris as your children. My husband expected me to do all the talking, but I had lost most of my vocabulary and was really tongue-tied (1983), so I sympathize with your children.

There is nothing like Yiddish for texture, we can’t quite translate it to catch the true richness. And all those other quotes are hysterical! Thank you for sharing them!

In defense of my kids, their level of French expertise was middle school at that point. And we don’t do a very good job of teaching foreign languages in public schools in our neck of the woods.

Those examples of twisted English are indeed hilarious Laurie. I plotzed indeed.

Things are so bleak these days that we could all use a few good laughs.

I love the conversation between your husband and the French hotel clerk. You would think the clerk would have moved on to say something else when Allo Oui was not working.

Re Yiddish words, In my experience, chutzpah and schmatte are more common than kvetch and mensch, so it’s interesting that you found them the reverse. And everyone I know says plotz. The classic use of schmatte is when someone compliments you on some beautiful new garment you are wearing, you are supposed to reply “This? It’s just an old schmatte!” I wish they had given a course in Yiddish when I was in college (as they do now), because I would love to know more than the handful of words I acquired growing up.

And thanks for the list of signs from other countries. Hilarious! I plotzed reading them!

You are right about the Yiddish. So many words have crept into our American lingo, and I agree about chutzpah. I’m not sure my non-Jewish friends know what a schmatte is. When my mother used that word with me, I knew she thought what I was wearing was really awful.

Love this story Laurie, but i’m sorry to hear that on that French trip your kids wouldn’t help you translate!

And your quotes are absolutely priceless!, but I don’t need that advice from the Japanese hotel – I always bathe inside the tub!

My kids contend, and rightfully so, that they never learned much French in French class. Sadly, that was true. My granddaughter (same school system) has taken Spanish since sixth grade and had her first native Spanish-speaking teacher her sophomore year of high school. She can’t say much of anything. Sad.

These are all great, Laurie, although I would have thought your kids would have relished speaking French to one-up you. Love your fractured translation list as well. When I was in Norway, I discovered that they learned British English. I tried in vain at stores asking for a pair of pantyhose, until finally, by accident, I noticed a sign for “Tights” and there they were. Yiddish words are a welcome addition to our vocabulary. Years ago I had a Filipina-American co-worker who asked me, one day, if I was Jewish. When I said yes, she asked, “What’s a meshuginah?” I answered her but was left to speculate about the source of her question.

Plotzed I did, Laurie! Just some terrific “lost in translation” examples. And Yiddish may be in many ways a dying language, but I do think many of its words and phrases have happily worked their way in to English — well beyond just among members of our “Tribe” — and with their meanings fairly well intact.

But I have to ask, exactly what did your husband think he was saying with “Allo oui”? Presumably, he at least knew it was not French for “chicken pox.”

He had no idea how to say “chicken pox” in French, nor in their defense did my kids. I have no idea why he kept repeating that phrase but it was pretty funny. I think he was just stuck trying to figure out how to explain our predicament. The important thing to him was to to be charged for the two days when we wouldn’t be there. Not only did that happen, but there was no change fee on our airline tickets. Obviously, things were much simpler back then.

One personal translation story has come to mind. Back around 1980 I was dating a woman (pretty seriously) whose Grandmother kept referring to me behind my back (but so I could hear it) as something I could not quite make out. Cindy would never tell me what she was saying. We lasted less than two years.

It was only many years later that I found out what “mieskeit” means.

That’s another Yiddish word I had forgotten. My grandmothers applied it liberally to many people, whether they deserved the label or not.