“If you misfile something it’s gone forever.”

The first step for new hires in the group was mastery of a seventy-page manual about alphabetization Seriously.

So said Archivist Harley Holden on the first day of my one-year tenure in the Harvard University Library system. Holden, a genial man, meant it kindly but he meant it. In time I learned to understand and appreciate it as the Cardinal Rule for collections. It was late summer in 1971, two months after graduation. I needed to find work to save money for law school and I wanted to stay in Cambridge, where my significant other would finish her senior year. I briefly stayed with a close friend and former tutor from my House who worked in the library, and it was he who suggested I look into it. Of course, “librarians” are professionals with advanced degrees, but it takes many more to operate a library, especially a university library. There was an opening in the Archives Department and I grabbed it. The standard work week was thirty-five hours then, and the helpful HR person who worked with me, knowing my plan to save for law school, suggested that I take a part-time position in the library’s Slavic Department to add an extra five hours a week. I took that, too. More about that later.

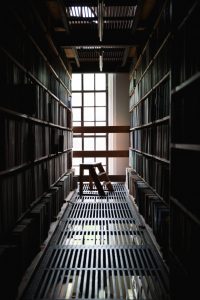

I was the most junior person in the Archives department. There was a receptionist/clerk and three professionals in addition to the Archivist. My responsibilities were simple: I was the one who retrieved – and then refiled – material from the dedicated library stacks in the interior of the canyon of Widener Library and from the subbasement catacombs. I was also tasked with relabeling an endless number of filing boxes whose contents would shift as more material was added. This meant spending much of my time in the aforesaid subbasement. But the relatively minimal demands of the job gave me time to see and explore the Archives’ holdings.

Being an Archives, the collection comprised not just books and written materials but memorabilia as well from the many eras of the university. I discovered that Harvard had played in the Rose Bowl, and won, in the twenties. I sifted through the posters, t shirts and pictures collected during the SDS occupation of University Hall and subsequent student strike just two years earlier.* I found I was easily distracted by this treasure trove, a fact tacitly acknowledged by the Archivist in a performance review when he complimented me on the quality of my work but regretted that he did not see a bit more production.

Perhaps the highlight of the Archives experience was access to the so-called “X Cage”. I only was there twice, the first when I was briefed by my predecessor and the second when I did the same for my successor. The X Cage was a locked enclosure within the locked enclosure of the Archives stacks. The key was in the custody of one of the professionals in the department, “Jean”, an older woman of indeterminate age with the mien of a classic schoolmarm. Which seemed fitting given that there were just two categories of items in the X Cage. The first was the ceremonial objects of the university, the official seal, chains, maces and the like. The second was reference material of a prurient nature. Strange bedfellows indeed.** I suspect that Jean took careful note of the elapsed time between retrieval and return of the key each time. She was the only one of us who referred to the enclosure as the X Cage. To the rest of us it was the Sex Cage.

A daily event was the retrieval of files from the student record room. In our formative years I believe we each heard mention of our “Permanent Record”, usually in the context of a warning about misconduct made to instill fear of eternal tarnish. Well, boys and girls, the Permanent Record exists, at least for Harvard undergraduates. Each such Permanent Record is an expandable file. The university administration, and only the administration, has authority to requisition it. Files for current students and recent graduates were stored elsewhere; all others were in the Archives. It was explained to me that in almost all cases the underlying reason for retrieval was an outside request to verify mundane details – dates of attendance and so forth. But the presence of these materials, and my access to them, made clear to me the reason that prior to my hiring the HR staff had performed some basic due diligence about me, a mini-security clearance if you will. Now, you might ask whether I ever took advantage of my access to these older Permanent Records. I am under no obligation to answer.

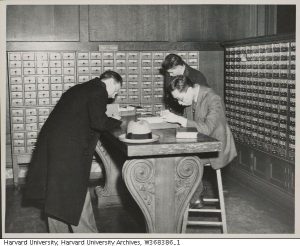

My work week in the Archives was nine to five with an hour for lunch. I started each day at eight in the Slavic Department. This was a dedicated unit for the collection from eastern Europe, including the then Soviet Union. The department had its own card catalogue, an enormous open bin that was my domain. My job was to file the transliterated cards representing the works added to the collection. Again, not too taxing but important because an important corollary to the Cardinal Rule is, if the reference card for the work is misfiled the work effectively is not within the collection. I think it helped that my unfamiliarity with Slavic languages made me pay close attention.

The staff of the Slavic Department numbered about eight, all professionals, mostly nationals from eastern Europe. And mostly very attractive young women who dressed to the nines. My tenure extended through the 1972 Winter Olympics and there was much friendly banter among the women about their respective national teams.

While my part-time work in the Slavic Department continued for my entire year, by the first of the year, 1972, I was growing tired of the mundane work in the Archives. The Archivist had done his best to make the job more interesting, including allowing me to do the initial intake of a new collection, but it was not sufficient.*** I paid a visit to my HR friend who told me of an opening in the Searching and Filing unit.

Searching and Filing is or at least was a division of the Catalogue Department. “Searching” was the first stage of the process: conclusively identifying the author so as to make sure that all references to the author were precisely the same in the catalogue. The unit comprised specialists in French, Spanish, Italian and German. I had a sufficient command of German to make the grade. The “Filing” involved maintenance of the card catalogue, which, in the case of the university library, was immense. New cards were added every day, both “finished” cards, i.e. those referencing works that had completed the cataloguing process and “placeholder” cards representing works that were or likely were to be in the acquisition process.

The first step for new hires in the group was mastery of a seventy-page manual about alphabetization. Seriously. A precise convention had to be observed in furtherance of the corollary of the Cardinal Rule. I remember none of it, but it was rigorous. The next step was supervised filing: the rookie would interleaf cards in the proper place in a drawer and leave the drawer out for the reviewer. Once the reviewer was satisfied the oversight ceased.

Typically we spent about an hour a day filing new cards. We were instructed to pull drawers out while in use rather than work with them in the cabinet so as not to obstruct library patrons, then reinsert them and move on. I found it easiest to pull out a drawer with one hand and pivot to place it on the table that separated rows of drawer cabinets, all in one easy motion. Thereby developing an occupational injury: stretched ligaments in my sternum. Mostly a nuisance.

Most of the rest of the day we spent in “search” mode: grab a stack of acquisitions, leaf through each book for identifying information, check the existing catalogue, and either confirm identity or flag the work for further review by a catalogue professional. There were eight of us, six young women and two young men. We all did English language books as well as handling books in our language specialty. We were also expected to use “best efforts” for related languages. I dealt with many Dutch books and dabbled in Swedish and Icelandic. It was not all that difficult to get the job done.

At the end of the day we spent time together, seated at last, in a room just off the card catalogue room, sorting through Library of Congress (LC) catalogue cards. While Harvard did not use the LC classification system, the LC cards had all the necessary information our cataloguers needed so they were a useful head start. But the Library Congress has many types of works that have no counterpart in a university library, so we separated cards that that were of no use from those that were. Not exactly intellectually intensive but we were off our feet and could talk among ourselves as we worked. And we developed a game of sorts: see who could find the most unusual or funniest or most ironic combination of title and author. I still remember my discovery that became the gold standard, a work entitled The Imperial Animal. The authors? Lionel Tiger and Robin Fox. Really. You can look it up.

A side benefit of working with this group was greater integration with other areas of the library, not just the cataloguers, all professionals, most of whom were truly interesting people, but also the reference librarians. I got to know one of them, “Jill” a bit and we enjoyed teasing one another. Like the time I discovered and scooped up an enormous shiny beetle in the yard in front of the library steps and took it to her for identification. She was a reference librarian, after all. She jumped back about four feet in the wink of an eye and without missing a beat said, “It’s a baby dinosaur, get it out of here.” Ah, library humor.

At last it was time to take my leave of the library and head to law school. But I fondly remember that time to this day.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* Earlier this year while in Cambridge I paid a visit to the Archives, now housed in a building built since my tenure. At the time, the fiftieth anniversary of the University Hall occupation and strike, the department presented a special exhibition of its pertinent memorabilia. I spotted quite a number of items I had first seen in my own private viewing years earlier.

** Maybe not so strange, the pairing of prurient written material with physical objects such as maces and chains. Fifty Shades of Crimson?

*** The project did generate a memorable moment. The collection was the papers of one William T. Reid, class of 1901, who had been a star baseball and football player and even a player-coach of the football team. Among his papers was a flip book showing a football player demonstrating punting. I showed it to the Archivist, who was quite excited to identify the player as the legendary Harvard coach Percy Haughton. I had made a real find.

Retired attorney and investment management executive. I believe in life, liberty with accountability and the relentless pursuit of whimsy.

A good view behind the scenes and beyond the stacks. Thanks.

Thanks Jean. I had forgotten how much fun it was. Who knew?

When I opened your story and saw the instantly-recognizable picture of Widener, it made me happy, even though I don’t think I ever set foot in that library in my four years of college. But hey, it’s the place where we take the class picture at every reunion!

Seriously though, I loved this story. That was an amazing job you had the year after graduation. Thanks for taking us on a trip through the Archives, the X Cage, and the Searching and Filing Division of the Catalogue Department. I’m glad to know about all those hidden places in Widener.

Thanks, Suzy. I recall going there exactly once. And if I remember correctly, being able to go into the “public” area of the stacks. For what, however, I have no idea.

This is really fascinating, Tom. I understand that it was dull work, but being behind the scenes of such a vast operation gives us some insight into how things were done in the days before computers sped everything up. Tedious to be sure.

I volunteered one summer in the library at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum, which at the time was a block from my house (this year it moved into a big newly renovated facility in a different town). I had absolutely no training, but was given the task to create a “Finder’s Guide” for three boxes donated by the Sea Coast Defense Chapter of the Daughter’s of the American Revolution. I looked for ways to categorize the various documents (with help from the professional who supervised me). I handled some interesting stuff including a letter from John Hancock, information about the charter that helped to create Martha’s Vineyard, a program from an opera singer “Nordica” who was an island native, Lillian Norton. She visited and sang a concert, which was BIG news on the Vineyard at the turn of the 20th century. I put everything into acid-free folders with labels that fit with the headings I had created for the Finder’s Guide and typed it all up. This was about 12 years ago. It gave me something to do while my daughter was at work in the morning. Not quite what you were doing, but still, cataloging in a library.

Thanks, Betsy. ‘Tis true. In those analog days things were much different. I wonder whether there are such things as physical card catalogues anymore.

Tom, I did go into Widener some time in the last few years. The space that used to house the card catalogue now has many computer terminals set to access online databases. Same purpose, current technology. I do wonder what became of the physical card catalogue.

I’m not surprised. Could be that all of the functions of my old unit have long since been automated. Back in the day we used to joke about dumping all of the cards down the elevator shaft. During the University Hall strike faculty members stood guard at Widener to prevent mischief. Of course nothing happened. Legend has it that to amuse themselves the ‘guards’ – all men – had a contest to see who could find the funniest graffiti in the library. The winner? Someone had written “my mother made me a homosexual.” Below that someone had written, ‘if I gave her the wool would she make me one, too?’

Bravo Tom, I was a school librarian and began my long career in the days of the card catalogue. By the time I retired, library catalogs were online and I had lived through the conversion from the old to the new.

But I must confess the day the school custodian carted away the old card catalog I felt I was losing an old friend!

There was something about the physical card catalogue. The picture in the story is of a portion of catalogue in the library where I worked. The room was quite large and there were six to eight banks of drawer cabinets. I remember well the aroma of the wood of the cabinets and the paper of the individual cards. Quite pleasant.

Understood!

This is really fascinating, Tom. I never had thought much about the workings of a world class library and the people responsible for maintaining its material. I assume much of this is computerized now. Hopefully, the old card catalogues are archived.

Thanks, Laurie. According to JeanZ (see below) the physical card catalogue has been replaced by a digital catalogue. I assume there is multiple backup of the virtual catalogue, so maintaining the superseded physical catalogue would be unnecessary. When I worked in the Searching and Filing unit and we sorted Library of Congress cards there were a fair number of discards. Our unit pioneered a program to recycle the cards, which were 3×5. Their highest and best use? Recipes. Think of all of the millions of recipes that could be recorded on the discarded physical catalogue cards!