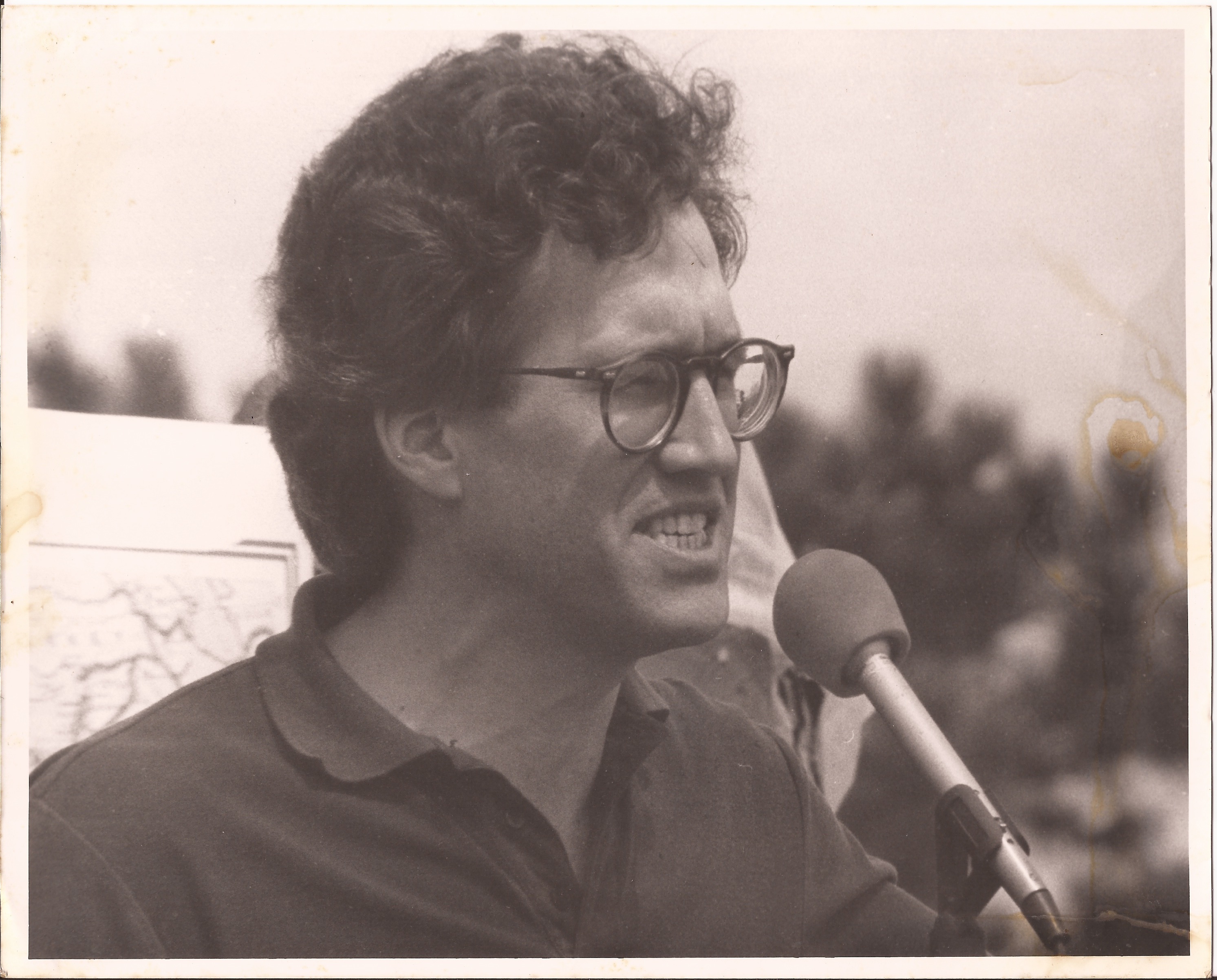

Ned speaking at an anti-apartheid rally at Purdue University, spring 1986.

Editor’s note: Our beloved classmate Ned Stuckey-French lost his battle with cancer on June 28, 2019. This story, originally written for CreativeNonfiction.org, was posted on the Retrospect prompt “Working” on September 4, 2017. The first paragraph made it seem appropriate to the current prompt, “Honesty,” so we have reposted it here. Ned was a smart, kind, generous man, a wonderful writer, and a champion of the essay as an art form. We will miss him!

In the fall of 1976, I lied on an application in order to get a job as a janitor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

In the fall of 1976, I lied on an application in order to get a job as a janitor at Massachusetts General Hospital. I left out the fact that I’d graduated from Harvard and done a couple of years of graduate work at Brown, claiming instead that I’d worked as an oil field roughneck, carpenter, liquor store clerk, trash collector, and groundskeeper. Indeed, I had done those things, but I stretched summer jobs to cover entire years and gave references that couldn’t be traced.

For the next decade, I worked at Mass General as a janitor and communist trade-union organizer, living a semi-secret life. I wasn’t the only one doing this: there were about fifteen of us at the hospital, trying to organize its several thousand workers into a union. Our larger democratic-centralist organization had cadres working throughout the Boston area—in the Quincy shipyards, the Lynn GE plant, the Framingham General Motors factory, a meat packing company, a steel fabrication place, and various community organizations. Nationally, there were hundreds of young, predominantly white, middle-class activists like us who had been politicized in the civil rights, antiwar, student, and women’s movements of the late ’60s.

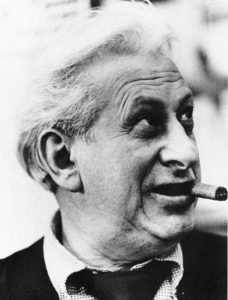

It was during this time that I first read Studs Terkel’s Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do (Pantheon, 1974). I read it, as did some of my comrades, because we’d grown up as students and were now studying how to join the working class. Though we’d find that proletarianizing involved more on-the-job training than book learning, Terkel’s interviews with more than 130 American workers were a great help.

Terkel, who had been blacklisted during the McCarthy Era, talked to a garbage man and a hooker about dignity. He talked to a meter reader and a postman about dogs. He talked to organizers, a receptionist, and a professor about talking. He talked to people who worked in factories and big offices, and he talked to people who worked alone—a piano tuner, a bookbinder, an elderly farmwoman who lived in a cottage on a mountain in Kentucky. He crossed the class divide and talked to a factory owner, a couple of executives, and a supervisor about being in charge. He talked to a few famous people—actor Rip Torn, New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael, and Washington Redskins coach George Allen—but mostly he talked to people who were unknown, giving them a chance to explain how they spent their lives.

Like Terkel’s workers, I filled my days at the hospital with routines: empty the trash cans; clean the bathrooms; clean up messes (blood, glass, vomit, and shit); sweep, mop, wax, and buff the floors. Like most of the people profiled in Working, I lived on a skimpy paycheck, had little job security, and received few benefits, but unlike most of them (the nonprofessionals, anyway), I had an out. I could take my white privilege and my Harvard degree and move on … as I eventually did.

My commie group cannibalized itself in sectarianism; at the hospital, we lost two union drives, and then the jig was up. We faced too much money and fear. But those years spent talking with people about their lives and learning to listen to them and working with them to write leaflets and organize meetings changed me. I’m a professor now, but not the same kind of professor I would have been if I hadn’t worked in the hospital—or at least I hope so.

Working changed me, too, in smaller but no less essential ways. Terkel’s book is a classic. Its people are real, rounded, and fully human. They disrupt our stereotypes: the garbage man plays golf every weekend, and the meter reader volunteers that his job would be much harder if he were black. Off-duty, they are reflective and unflinchingly honest. “You were the lowest of the low if you allowed yourself to feel anything with a trick,” says Roberta Victor, a prostitute since the age of fifteen. “The bed puts you on their level. The way you maintain your integrity is by acting all the way through.” Terkel told Chicago magazine that his method was no method at all. Mainly he just listened, but with real interest. “I don’t have written questions,” he said. “It’s a conversation, not an interview.”

I suspect that when I first opened the book back then I jumped ahead to Bill Talcott’s section. His title was “Organizer,” and that’s what I wanted to be. He says:

My work is trying to change this country. This is the job I’ve chosen … I try to bring people together who are being put down by the system, left out. You try to build an organization that will give them power to make the changes.

Of course that resonated. Now, it sounds a little grandiose—still worthy, but grandiose. I could never be a working-class hero. A déclassé revolutionary, perhaps, but objective conditions would have had to be ripe for a revolution, and they weren’t. Instead, Studs Terkel and the hospital took me outside myself and my class, if only for a while, and for that I’m ever grateful.

“A Real-World Education” was originally published in the Fall 2015 issue of Creative Nonfiction.

Ned Stuckey-French teaches at Florida State University and is book review editor of Fourth Genre: Explorations in Nonfiction. He is the author of The American Essay in the American Century (University of Missouri Press), co-editor (with Carl Klaus) of Essayists on the Essay: Four Centuries of Commentary (University of Iowa Press), and coauthor (with Janet Burroway and Elizabeth Stuckey-French) of Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft (Longman, 9th edition). His articles and essays have appeared in journals and magazines such as In These Times, The Missouri Review, The Iowa Review, Walking Magazine, culturefront, Pinch, Guernica, and American Literature, and have been listed six times among the notable essays of the year in Best American Essays.

Visit Ned's website: nedstuckeyfrench.com

As a Studs Terkel fan, I loved this story and I admire that you stayed with the hospital job for ten years. I once took a job in a garment factory just to learn about it. This was in 1960 and we were making ammunition pouches. Management assigned me to a bar-tack machine that jammed itself every three to four minutes. This was assembly-line work, with quotas to meet, and the only way to dislodge the jam was to stand up, insert a wedge, and give it a whack! I brought this problem to management twice in my first week, but they were unconcerned. When I told them I was quitting, they offered to place me at some other post, but I was really done with them. My next job was in a library with windows and fresh air.

Ned, I so admire you for doing this. If I had known about it, I might have wanted to join you, although by ’76 I was 3,000 miles away and going to law school. Great story, weaving together your experiences and Studs Terkel’s incredible book. Thanks so much for sharing it with Retrospect!

Thanks, Suzy. We needed progressive lawyers then and we need them now. Onward.

Thanks, Jeanne. Garment factories, libraries — it all needs doing.

Thank you for sharing this interesting and important slice of real work and union organizing with our community. The world seems very different today.

Thanks, and yup, the world is very different, though, I suppose, also much the same.

Don’t look now, Professor Stuckey-French, but your knowledge, skill, expertise, commitment, compassion, and eloquence are showing! You used the topic, your experience, and Stud Terkel’s work beautifully to connect the dots between New Left politics, humanity, and the oft-forgotten deep organizing that fostered significant so many societal changes. You also contradict the myth that our movement(s) failed. Out of efforts like yours came feminism, a new style of organizing, environmental awareness, massive educational reform. To cop a cliché, ‘it was a tough job, but somebody hadda do it.’

It was also a pleasure to watch you ‘preach’ what you teach. Such a well-written essay. If it’s okay with you, I’d love to use ‘A Real-World Education’ in a class discussion at CSULA!

Thanks for those kind and generous words. Of course, Charlie, I would be honored to have the piece distributed and discussed in your classroom. Hope it get ’em thinking. Thanks again.

My condolences to all who knew Ned. he sounds like a remarkable man.