Dumbarton Bridge that crosses the San Francisco Bay near Menlo Park

Sixteen years may not seem like an extraordinary long passage of time prior to reconnecting with someone you once knew. But it is if you are just 21 when you track them down. That was the case when I visited Velma Bates in 1971, at her home in Menlo Park, in the San Francisco Bay area. Of several women whom my parents had hired to help around the house and with the care of the kids in our family when I was young, Velma was the one I had always remembered as my favorite. By the time I looked her up, I no longer remembered the reasons. I just had a warm feeling about her. I knew in my heart and my memory that we had truly enjoyed one another’s company, and I wasn’t going to pass up the chance to see her.

She didn’t seem thrown off by how forward I was, or by the fact that I had not bothered to give her any advance notice I was even going to be in her region of the country! Or by the suddenness of this entreaty following a gap of 16 years.

I did not make the trip out to California from Indiana just to see Velma. I was out of college for two full semesters between my junior and senior years, living at home and working for most of that time. I was eager to do something more adventurous with the remaining time, so I made a plan to see the West, travelling mostly by thumb. On the Road by Jack Kerouac had come out in 1957 and Tom Wolfe’s Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test in 1968. I wanted to merge with those meandering streams of youth, hitchhiking around and looking to a place to “crash” for a night or longer.

My parents were originally from Ohio and our vacations had always taken us east, mostly to see relatives. On rare trips that did not involve visits to family, we went south. These latter trips invariably included stops at Civil War battlefields, which was not my parents’ idea but that of my older brother Leon. He developed a keen interest in the Civil War at age ten—foreshadowing his later career as an American historian–and was very good at influencing Mom and Dad’s decisions. I am pretty sure they consulted him quite seriously before buying a 1956 green Ford station wagon that would become our family car for the next six years. For certain, it was due to his influence that our family spent a day touring the Battle of Vicksburg on the only visit we ever made to Uncle Bud, my Dad’s brother, in Jackson, Mississippi. It was also why we stopped for a day and a night in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania on the way to the Jersey shore, where Uncle Stan lived. And it was the reason our route to see the famous sites of Washington, DC, veered off to include the battleground of Chancellorsville.

I was aware when planning my trip that nobody in my family had ever been west of Chicago—not even my Dad, on travel related to his law practice. It felt like a big deal that I was going all the way to California.

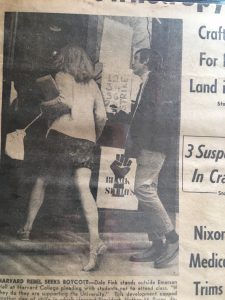

A newspaper photographer captured me (and misquoted me) on a picketline during the 1969 strike at Harvard.

Velma’s contact information was part of a considerable list I put together as I cast a wide net and collected addresses and phone numbers I might need. To live on my anticipated budget of $200 in Traveler’s Checks plus another $30 or $40 in cash (and no credit or debit card) and make it last for three or four months, I would end up needing just about all of them, for free lodging and (I realize sheepishly in retrospect) for quite a few meals subsidized by others. Reinier, a college friend from California, was nice enough to give me the name of a buddy of his in in Isla Vista—home of the University of California at Santa Barbara—where he said I would be welcome if I mentioned his name. I did call the buddy on about an hour’s notice one day and he put me up for a night. Reinier also gave me his home phone number and encouraged me to visit his mother in Santa Monica. When I called on her, I did not actually come with the expectation of spending the night, but after feeding me dinner, she recruited me to watch a late-evening black-and-white movie on TV, and I ended up accepting her gracious hospitality and crashed there as well. There was Sally, whom I knew from high school and from synagogue and who was nice enough to share her dorm room with me at the University of Colorado (Boulder). Dana, a girlfriend of Sally’s, found me a couch for a few days at the University of Utah (Salt Lake City). I crashed for a week at a commune in Portland, Oregon, with a friend named Madeline: like me, she was taking a year away from Harvard-Radcliffe.

My longest stay was in the San Fernando Valley outside Los Angeles, at the home of my dad’s lifelong friend Hugh Reilly. Dad and Hugh had met when they entered Northwestern University in 1937. My parents named my younger brother after him. This violates the Jewish tradition of naming only after those who have passed, but there might be some kind of rabbinic waiver for naming after an Irish-American who learned Yiddish while growing up in Newark, New Jersey. Without my dad calling Hugh Reilly and clearing the way for me to treat his place in North Hollywood as my home for as long as I wished, the entire trip would not have been feasible. I ended up spending several weeks at the Reilly home, although Hugh himself was away, acting in a soap opera in New York City.

My outreach to VeIma was different from the rest. I viewed just about all of the other contacts as instrumental to my broader purpose of being on the road, discovering the West. Meaningful human connection arose as a by-product of some of these visits—for instance, with the youngest of Hugh Reilly’s three sons, Ethan, who was in middle school at the time. But reconnecting with Velma Bates was an end in itself, not a means of advancing down the road apiece.

My call to her came after I had spent a few weeks in LA, then thumbed up to the Bay Area and spent a couple of weeks there. I had slept for several days on a couch on the main floor of a communal living situation near the heart of Berkeley—the residence of Paul Moore, whom I knew because his parents and mine had become close when they lived in Indianapolis. Then, wanting to spend more time on the other side of the bay, I called Alvin and Robin, who had been one of my rides hitching up from LA. They really enjoyed my rendition of the 1950s tune, “Chip Chip” (also known as “Mansion of Love,”) when I sang it from their backseat as we headed up the 101 North. They had given me their number and when I called, they were happy to put me up for a few nights. My travel journal tells me their second-floor apartment was located at 22nd and Dolores. That’s located in a section of the city called Dolores Heights, abutting the Castro district (says Google Maps).

I called Velma when I felt I had explored San Francisco to the degree that my budget and lack of transportation would allow. I would soon be ready to head farther north up towards Oregon and Washington. The newspaper headline the day I called her announced that Lt. William Calley had been found guilty in an Army court martial for the 1968 massacre of dozens of Vietnamese civilians at My Lai. That was March 29, 1971.

I called velma on short notice—same as Reinier’s buddy, Reinier’s mother, Sally, Dana, Madeline, Paul Moore, and all the rest. It was about 5;00 pm.

“Hello, is this Mrs. Bates?”

“Yes, it is.”

Uh…,my name is Dale Fink.”

“Who?”

“Uh, Dale Fink. Is this Velma Bates?”

“Ye-e-e-sss! Oh, Dale, how nice to hear from you. Where are you?”

I explained that I’d been out west for a couple of months and was calling from San Francisco.

“Well, are you going to come and see me?”

In this photo, Leon is at left and I am the babe-in-arms, with our dad and mom. It was about a year later that Velma came to work in our home.

“Well, I want to. I was thinking I could take a train there tonight if it’s a good time…um, in fact, if you could put me up for the night on a couch or something, I could just bring all my things–my suitcase and sleeping bag from where I’ve been staying.”

“Of course.” She didn’t seem thrown off by how forward I was, or by the fact that I had not bothered to give her any advance notice I was even going to be in her region of the country! Or by the suddenness of this entreaty following a gap of 16 years.

“My house is not very clean,” was her next statement. I didn’t have time to pause at the irony that I might be forcing someone who had cleaned our house for a living to now feel that she had to clean her own house—for my benefit. “Oh, you know, you don’t have to apologize about that! I just would be really happy to see you.”

“Well, I’d love to see you too.”

She thought taking a bus and getting off at Palo Alto, the next town over from Menlo Park, would make more sense than a train. It looked like I should be able to make it there in about two hours if I hustled back to get my things and headed quickly to the bus station.

Unfortunately, Robin gave me directions to what turned out to be the wrong bus station. I took a city bus there and discovered that the San Jose bus, the one I needed—was leaving from a different Greyhound station. It wasn’t far away, but required taking another city bus,and when I got off the bus and ran to the depot, suitcase and sleeping bag flapping all the way, I saw the San Jose bus pulling away. Too late.

There would be another bus in an hour, but I decided to see if I could hitch a ride sooner. My understanding—from my mom, who had stayed in occasional contact with Velma and provided me with her phone number—was that she still did domestic work full-time and would probably have to get up and work the next morning. Not very nice of me to arrive any later than I had planned. I walked to an entrance to the 101 South and stuck out my thumb. I had to wait 20 minutes but finally lucked out, getting a ride from a man with well-trimmed facial hair who looked to be in his 30s. Pat worked at Stanford’s famous electron accelerator in Palo Alto and serendipitously, was heading to the Menlo Park exit. He was divorced and picking up his two kids there. (Yes, some drivers really open up to hitchhikers. And it helps to keep a journal, if you plan to write about it 50 years later.)

Pat dropped me off at a mini-shopping plaza near the Expressway where there was a pay telephone booth and a liquor store, and I gave Velma a call. A few minutes later, I was seated in the front seat of her car. We hugged and kissed. She was about my parents’ age—fifty, or early fifties—with an average-sized frame, and wearing glasses. She said I looked the same—which struck me as remarkable. It crossed my mind that she had missed my entire span of wearing thick glasses from ages 7 to 17, since I had switched to contact lenses when I started college.

Velma told me on the way to her house that she was doing domestic work three days a week and took in roomers, two or three at a time, to cover her expenses. We pulled up to her modest but comfortable home with a well-tended yard, and she introduced me to the married couple who were currently boarding with her—a 27-year -old man and his 19-year old wife. Her third current roomer was not there, and would not be back for a few days, so she gave me his room. I used my sleeping bag on top of his bed so as not to disturb his sheets and covers.

Velma let me know, with what seemed like regret, that her second husband was in the process of divorcing her. They had purchased a lot in Tucson and put a mobile home on it where they spent time during breaks; she loved it and showed me photos. But he was taking that as part of their settlement; she would keep the Menlo Park house along with their camper-trailer. She said later the thing she missed most was having nobody with whom she could go fishing—that’s what she and her ex used to do with the camper-trailer.

Not being from a family that is good at building or fixing things, I was impressed that Velma was expecting delivery of a load of bricks and some mortar in a couple of days to construct a walkway. I asked where she acquired the skills for that kind of work, and she replied matter-of-factly that she went to the library and took out a book on masonry. She had used the same method to handle a lot of her own plumbing. On top of these house-related skills, she had been studying Spanish, in hopes of finding a job in health care, given that so many of the patients were Spanish speakers.

Once she updated me on her situation, it was time for us to talk about my family; or more specifically, the other member of the family with whom she had the greatest interaction. “Tell me what Leon is like now.” She only truly knew Leon and me and my parents, since Elaine was one year old when Velma left Indiana, and Hugh and Laurel were born in later years. Much of the time that Leon and I hung out with Velma coincided with the times Mom was nursing and taking care of Elaine, while my Dad was downtown at his law office.

I tried to piece together my older brother’s story—all the years since he turned eight—in some kind of coherent trajectory, but that was not easy. I said he was more serious than I was about academics, and that he had now entered graduate school at the University of Rochester. I mentioned that he had a serious girlfriend for a couple of years but it’s been over for a while. I was stumbling to say more, when she cut in.

“Is he purty?”

Back then, and even now, I associate that expression—calling a man pretty, or more colloquially, purty, with Muhammad Ali, who spoke frequently of his own pretty face and how he wasn’t going to let it be messed up by any challenger in the ring. It made me smile. “I guess so.”

We continued the conversation over TV dinners (I had to object strenuously to keep her from heating up two whole TV dinners just for me), followed by pieces of a store-bought pie she took out of the freezer. She said that after a lifetime of cooking for others and for two long marriages, she was through with cooking. “Whoever invented TV dinners sure was a smart man!” was one of her comments I recorded in my notes later.

“Do you want to watch TV?” she asked, as we finished dinner.

“I would rather just keep talking.”

“So would I,” she beamed. “Just tell me when you get too tired. I know you’ve been travellin’ around and that’s tiring.”

She insisted on hearing news about my parents, whom she called “Mr. Fink” and “Mrs. Fink,” and Elaine, Hugh, and Laurel. She told me she had “only seen Mrs. Fink cry” one time, and it left an impression on her. It had something to do with one of her brothers (Aleck, Sam, or Leonard)) getting turned down for some kind of job or opportunity, and he was pretty sure it was because he was Jewish. After telling me that story, she volunteered that she could always tell if a family she worked for was prejudiced. She “never saw a trace” of that in our family.

The most memorable part of our conversation—the part I’ve always remembered even before I went back and reread my travel journal—was her discussion of the dynamics between her and Leon and me. Someone else who previously worked for my parents forewarned her that Leon—who would have been four when I was two at the time Velma started– could be a handful. She arrived, ready to ponder the situation and figure out a workable approach. Leon, she soon confirmed, could become very irritable if he didn’t have his way. She characterized me, on the other hand, as a sweet and willing follower. She said she learned from my example. “You always did whatever Leon wanted to do. I found out that if I also did whatever Leon wanted, then we all three could have a good time together.”

The three of us had some picnics in the good summer weather. Leon began “nagging all fall and winter about going out for a picnic like we had before.” One day, when there was snow on the ground, he persisted in his demands that we go for a picnic. She gave in and got us both bundled up in our winter clothing, brought some hot chocolate in a thermos, and walked us a few minutes away to an area that was a gravel pit back in the 1950s. (It would later be turned into luxury private homes.) We all sat down at what she described as the foot of a sand hill, covered in snow. She poured out three cups of cocoa.

According to her recollection, Leon said, “This is fun, isn’t it, Velma? This is lots of fun, don’t you think?”

“Well, yes, Leon,” she answered, this is really nice. I’m havin’ a good time…don’t you think so, Dale?”

She said I looked around at her and Leon, holding my cup of cocoa in my three-year-old hands. “I’m cold.” Velma nodded her head and acknowledged that she was also cold, and looked at Leon,

“I’m cold too,” Leon said. “Let’s go home.” And we all trooped back to the warm house.

The next morning, a Tuesday, I got up early, knowing that Velma was supposed to be at one of the homes where she worked at 8:00 am. I wanted to be able to have breakfast together and share a bit of conversation before I headed north. She was wearing her working whites, and had prepared a delicious breakfast of bacon, eggs sunny-side up, buttered toast, and a hot cereal that reminded me of grits but had a different name. As we began to talk, she asked what I planned to do. I traced out my plans vaguely (because I wasn’t at all sure of them). She asked, “would you like to stay on?” I said sure, but I did not want to mess up her work schedule. She explained that she could probably change today’s commitment to Wednesday, unless the “old man” was experiencing some unusual difficulty. She called the family, explained about my surprise visit, and they told her to switch the day without any worries.

We agreed it would be fun to get out into nature. She changed out of her work clothes and we headed off to take a walk at a duck pond. After that, she drove me to the interior end of San Francisco Bay, where there was a nice view near some kind of military base. We sat in the car, enjoyed the view, and spoke of ecology, pollution, my experience in the earthquake in the San Fernando Valley a few weeks earlier, and among other topics, how beautiful she thought the freeways around LA looked at night.

We got on the subject of the Viet Nam war. She knew about some of the soldiers who were turning their guns against their own officers rather than the Vietnamese. In almost any other context, she was against violence, but she respected those soldiers. “I would do the same,” she said. I told her about my roommate, Doan, who was from Viet Nam and had invited me to visit him some day in a peaceful, reunified, socialist Viet Nam.

She returned to the topic of studying Spanish. She told me if she continued to master it, she would be able to speak it correctly. “And that’s something I never could do in English,” she said. Because, she said, she grew up in Tennessee, in an illiterate family.

We stopped at a small grocery store on the way back to her place and at her invitation, I picked out a can of Old Fashioned Vegetable soup for lunch. She knew the owner of the store, and when she saw him, she said, “there’s someone I want you to meet. This is my son, Dale…I helped raise him back in Indianapolis.”

I relaxed in the living room while Velma heated up the soup. She emerged from the kitchen to ask, “Dale, how many hot dogs would you be able to eat? I’m making wieners and beans.” At age 21, I was only familiar with eating one hot dog at a time—usually in a bun—and sometimes having a second one, depending on whether this was a cookout that included both burgers and dogs. I had never eaten more than two at one meal, but something about the way she put the question let me know that I should ask for more than two. So I replied, “I guess I could probably eat three.”

“Dale, you’re a man now! I’m not going to serve you just three hot dogs! I’ll tell you what: I’ll make the whole package, and you eat just as many as you want!” And nearly the whole package of eight is what I ended up eating, along with the canned beans and the soup.

Earlier, Velma had shown me her Swahili workbook. It was from an evening course offered through a Black Studies program at the local high school. The class was cancelled after the first few meetings due to insufficient enrollment, but she was continuing to practice the words in hopes of signing up again in the future. As she pronounced some of the words for me, they sounded truly melodious.

She dropped me near the Dumbarton Bridge, the southernmost crossing of the San Francisco Bay. There is a one-way toll collected from passengers heading west from Fremont back to Menlo Park, which in 2021 is listed at $6.00. Back then, Velma told me she preferred not to drive me across because she would have to pay a 25-cent fare to return.

An offer of a ride came quickly, and the driver would take me all the way to Oakland. He was an African-American just a bit older than I, who turned out to be a student at Stanford. Once he found out I was out of college because I had been suspended after obstructive picketing during the Cambodia invasion, he launched into some revolutionary rhetoric.

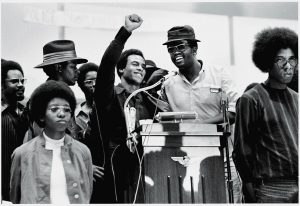

Black Panther Party co-founder Huey P. Newton (1942 – 1989) (center) smiles as he raises his fist from a podium at the Revolutionary People’s Party Constitutional Convention, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, early September 1970. (Photo by David Fenton/Getty Images)

He talked about the movement to free Black Panther Chairman Bobby Seale, and the current situation of Defense Minister Huey Newton (living in an expensive penthouse, which did not sit well in some quarters of the Black movement). My driver was all for the penthouse: “We don’t want anymore dead martyrs!” He kept up a rapid stream of strong opinions, even asking me at one point if I was “ready to pick up a gun.” (I wasn’t.)

I listened to him and participated in the dialogue, but my mind turned back to Velma. The window through which I looked at her had broadened. Velma’s words and life story had more power at the moment than this peer, with his angry rhetoric. I thought about the lifelong walk towards freedom and dignity in which she had engaged. From a childhood in Jim Crow Tennessee to doing domestic work, which included taking care of my brother and me, to mastering practical skills such as masonry and plumbing and Spanish, and now embracing the spirit of Black pride and Pan-Africanism through her study of Swahili.

Velma wrote to Mom after my visit. She related that she looked in her rearview mirror as she drove away and watched as I got smaller and smaller. She thought of my family and prayed that I would safely return.

Dale Borman Fink retired in 2020 from Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, MA, where he taught courses related to research methods, early childhood education, special education, and children’s literature. Prior to that he was involved in childcare, after-school care, and support for the families of children with disabilities. Among his books are Making a Place for Kids with Disabilities (2000) Control the Climate, Not the Children: Discipline in School Age Care (1995), and a children’s book, Mr. Silver and Mrs. Gold (1980). In 2018, he edited a volume of his father's recollections, called SHOPKEEPER'S SON.

You had a remarkable connection with Velma, Dale. You paint a portrait of a strong, determined, capable, lovely woman. She pulled herself up, educated herself, while caring for others, but she still cared for you and considered you family. A truly heart-warming story, even all these years later. Did you ever get in touch with her again, or find out anything more about her?

That was the last time we had contact, as I moved on with my too-busy life. It looks like she lived to 95, which would have been just a few years ago, from something I found on the Internet. (Dad also died at 95 and Mom at 96 so all around the same years.)

What a great story, Dale. I loved getting to know Velma in such detail and am really impressed by what she made of her life. The small points in your story have a lot of meaning for me, having lived in Menlo Park four separate times from 1979 to 2000.

Thank you for introducing us to Velma. I can now see why you would have wanted to track her down — back when finding people was so difficult — and I am delighted that you not only got to see her, but had such a lovely visit. Indeed, I always worry that such visits are going to go horribly wrong.

More than that, Velma sounds like an incredible person and I am so glad you were able to learn so much more about her, and her depth and skills and thirst for learning, from your visit. And that she was a truly loving person. I have often thought, as a privileged white person, had I been born Black and subjected to all that meant at that time (and, sadly, still means), I would not have been half the person that Velma was. I just hope that she had some true happiness in her long life.

I enjoyed this story about Velma, as well as about your adventures thumbing around the West during your “sabbatical” from college. I particularly liked the way you start out – 16 years isn’t much to us now, but if it spans the years from age 5 to 21, it is huge!

It’s not surprising that you don’t have any pictures of Velma, either from your childhood or from your 1971 visit, because that was before we all had camera phones in our pockets at all times. But I’m struck by your decision never to tell us that Velma was Black until the penultimate paragraph, and even then only obliquely. Once that was revealed, I went back to the paragraph where she introduced you to the shopkeeper as her son, and wondered what he thought about that.

I thought many would read between the lines–based on the name and her having been a domestic worker–that she was most likely Black. But it didn’t seem important to me to spell it out prior to the ending. I am hopeful it works, regardless of what ethnicity the reader might imagine.

On a separate note, I’m so happy you commented on that opening sentence and that you gave me the thumbs-up. I probably rewrote it (variations on that same theme) about a dozen times, trying to get the rhythm as well as the meaning of the sentence just the way I wanted it.

A very caring story, Dale, and I like how you bookended the ending with the window to the broader view you now had of Velma and the smaller and smaller view she had of you in her rear view mirror. Well told.

It’s great to have a reader who notices some of the smallest touches–even ones the author wasn’t necessarily thinking about consciously!

I am blown away by the detail of this story, Dale. How wonderful that you kept a journal (and didn’t lose it over the years), and also that you were able to reconnect with Velma. She sounds like a remarkable woman.

I’m late to the party, Dale, but what an amazing narrative. You have a true gift, and clearly pay attention to detail. I note you were careful to refer to THE 101, California style. And Reiner: would that be Reiner Kraakman? He was in my Hum 75 section freshman year. He was impressive. I remember one class where the professor, Jack Stein, sat in. He, too, was impressed and urged Reiner to concentrate in German.

Thanks, Tom. Yes, that was R-E-I-N-I-E-R (it’s a pallindrome) Kraakman. Good guy. TEaches at Harvard Law. Had one B. Obama as a student!

p.s. You were NOT late. I didn’t finish and post the story till Wednesday.

Tom and Dale, I feel compelled to point out that referring to a freeway as THE 101 is not California style, it is Southern California style. We in the northern part of the state find that practice absurd! We always know when someone comes from LA, even if they are now living in the north, by their use of that article.

I stand corrected. You’re right: our investment management conglomerate had offices in Pasadena and SF and now that I look back it was only the Pasadena folks who used the term. I had a sculptor friend when I lived in the Adirondacks who had grown up in SoCal and spent her early career there. She brought the habit with her, referring to our own major NY highways as “the 9” and “the 87”.

Wow, Dale! I feel like I was On the Road with you back in ’71. Thanks for the ride;-)

I especially liked the vignette of the picnic with Leon and Velma and you. You were brave to admit you were cold to your older brother. And your candor, though I’m sure at that age you didn’t consider what you were doing, brought your brother around. Or maybe gave him a way to go home and save face.

Anyway, I enjoyed reading your piece about your sweet, strong connection to this older woman;-)

Thanx Dale for this very moving story of your reconnection with a woman who’d been so good to you. Children don’t forget kindness and Velma’s kindness was returned during that visit.

As always I’m amazed at your recall of dates and details and now I learn you keep travels diaries, bravo! Stay safe until we can travel safely once more!