The first time Delilah slept over, I felt sheepish and almost ashamed, slipping out of bed before she was awake to begin the floor exercises my chiropractor had given me for my back. Pulling on a pair of sweatpants, I began a brief series of stretches while attempting not to awaken her. At age 24, I wanted her—or any woman I might bring home–to think of me as a strong, manly guy, not somebody with such a severe back problem that I had to do these stretches before we could even go downstairs for breakfast,

“My ex-husband thought of himself as a ‘breast man.’” She paused. “What have I gotten myself tangled up with here? A ‘floor man?’”

I should note that I have given this ex-girlfriend a pseudonym. I am satisfied it’s a good one, because her actual name had three syllables and, like the Biblical Delilah, she once gave me a haircut.

She awoke in spite of my effort to suppress any sounds. Flicking her long brown tresses off her face, she craned her neck to smile down at me curiously,” I’ve been with a guy who thought of himself as a ‘leg man’,” she said, speaking just above a whisper. “My ex-husband thought of himself as a ‘breast man.’” She paused. “What have I gotten myself tangled up with here? A ‘floor man?’”

Delilah was funny: that’s certainly one of the reasons we were dating. It’s also one of the reasons my roommate Dave, the software engineer, would begin dating her after she and I stopped seeing each other. With Delilah around, laughter was pervasive.

Maybe Delilah could laugh a lot because she did not have the same level of stress as most of the other parents who enrolled their children at Wesley Child Care Center in Dorchester, where I was a teacher. She came from an educated, suburban family and had parents who could still help her out with money or taking care of her son Alex. For another, she had a better-paying job than a lot of the other moms. She. worked the night shift at the First National Bank in Boston (later to be known after an acquisition as BankBoston, then Fleet Boston Financial, and ultimately, Bank of America). The work Delilah performed at the bank—and she was very proud of this–was operating a check-sorting machine. It paid an excellent hourly rate but required a lot of lifting and dumping of heavy bags and getting one’s hands and fingernails dirty. It had been considered a job only men could handle, until she insisted on being given a chance to do it and they had no legal recourse to deny her the opportunity. She eventually got herself assigned to three twelve-hour shifts per week, which meant she looked totally exhausted and groggy if she was coming off a shift, and really refreshed the rest of the time.

I was embarrassed about my condition, so I couldn’t laugh in spite of Delilah’s good humor. I tried to make it sound trivial as I explained about my recent episodes of back pain. I told her I was committed to this brief series of stretches that Dr. Anderson had given me. I also explained about taking hot baths each day, as hot as I could tolerate it, followed by 30 minutes of lying supine. I was so sorry if I was killing the fun, but I was supposed to do the exercises first thing every morning, and truthfully, I would do anything to avoid having that terrible wrenching pain return and screw up my young life.

Delilah’s most frequent smile was an impish one, and she leaned into one of those now. “Well, I’m impressed,” she said. “Impressed? In a good way or a bad way?”

“It probably seems like a terrible kick-in-the-pants,” she said. “I mean having a back problem at your age. But your response is so disciplined.”

“Well, this is already the second recurrence, and I don’t want another one.”

I didn’t tell her, but there had been a few times when the lower back pain had kicked up so much that I couldn’t go to work. As a matter of fact, there was a time when I couldn’t even answer the telephone. This was before the era of answering machines or voice mail. The phone was ringing only a few feet from my bed, but I could not succeed in rolling over and navigating my way over there before the ringing stopped. There was no way to find out who had been trying to call me.

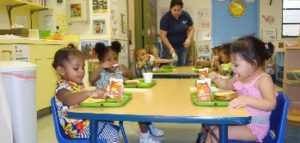

There had been days when I went to work but never sat down over the course of my seven-hour shift. Standing was tolerable but sitting was not. The three members of the teaching team ate lunch along with the children, each of us seated at one of the three rectangular tables that the “helpers for the day” had set with disposable plates, cups, and utensils, I remained standing at the head of my table while I ate, holding the paper plate in front of me at waist level—a bit awkward, but I explained the reason to the children and they accepted it. .

After lunch, we had story time. I recall a day it was my turn to be in charge. From a standing position rather than seated on a chair, I read a book and showed the illustrations to our group of fifteen four- and five-year-olds. At least there was no one clamoring to sit on my lap that time: even preschoolers can recognize that a person standing has no lap.

When it was time for the kids to lie down and take their naps after the story time was complete, I lay my 5-foot, 10 inch frame on one of the preschool-sized cots for a few minutes of respite.

That had all happened the previous year when the pain had been at its most severe. That was prior to the time Delilah’s son Alex had entered my classroom, months before I had my first substantive conversation with her–the day she accompanied us in the daycare van on a trip to pick apples at an orchard.

The reason why I had a back problem was not a mystery to me. It was because of my union organizing efforts. I was active in a grass-roots union movement, trying to organize teachers and others who worked in daycare centers all around the Boston area. The back problems, as best I could tell, were a direct consequence of all those meetings in people’s apartments, sitting on the floor for hours.

I had met a guy named Johnny in 1973. He worked at the campus daycare center at Tufts University. Like me, he had been an activist against the Viet Nam war. And like me, he had gone into day care work for the love of supporting young children’s learning and development. He had been similarly startled to discover how puny was the remuneration, how pitiful the benefits. We started talking to “friends of friends” and within a few weeks identified a corps of day care teachers from eight or nine different centers and pulled together our first meeting. We all agreed we needed to organize to gain more livable wages and conditions, and to gain a voice in our emerging profession—because the state was only beginning to create licensing regulations and to consider various pathways toward funding. We called ourselves BADWU, the Boston Area Daycare Workers Union; a year later, we modified our name so that the U stood for United. For the remainder of our existence, we were the Boston Area Daycare Workers United.

BADWU eventually grew to encompass upwards of sixty active members from perhaps 25 different centers around the area. We had a Classroom Issues Discussion Group for people who wanted to discuss the social and political values we were conveying to preschool-aged kids: How do you promote nonviolent conflict resolution? How do you generate respect for people of different racial and cultural backgrounds? How do you challenge traditional gender roles? How do you promote child-centered classrooms, where children made choices and expressed themselves, as opposed to each child making the same teacher-designed art project and reciting the same dreary ABCs every day?

We had a Political Issues Group for those wanting to gain input into the state’s regulatory and licensing practices, and to support legislation that would bring more funding into our field. We had a Workplace Organizing Group to focus on grievances teachers told us about: directors changing people’s schedules at the last minute, requiring extra unpaid hours for working on the classroom or attending meetings, teachers who were expected to leave the classroom and answer the phone in the office if it rang while the director was out. And then there was a Steering Committee, to set the direction for all our activities. Johnny and I were ex officio members, being the founders, but we were always looking for women leaders who could displace us, given that over 95% of the workers we were trying to organize were female. Eventually, we found Nancy—or as some called her, “the Norma Rae of the daycare workers movement”—but that’s a story for another day.

With organizing came endless meetings. I didn’t understand yet about the physical toll those meetings were taking on me. None of the people I knew who worked in daycare centers lived in places with large living rooms or ample furniture. Our meetings took place in sparely decorated houses or crowded apartments in Brookline or Allston or Cambridge or Somerville or Dorchester, with most of us seated on the floor.

I had started working part-time in a daycare center in Cambridge, Massachusetts, while I was in my final year of college, in 1971 to 1972. When I graduated, I took a position as a full-time assistant teacher—just for the summer, to replace someone who went on maternity leave–at a daycare center in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston. When that job ended, I found a similar position at the center in Dorchester where I continued for over four years.

The work was way underpaid and very demanding, but I found it incredibly satisfying to involve myself in observing and supporting the emotional, social, physical, and intellectual development of young children. No two days—no two hours– were ever the same. Children were endlessly fascinating, inquisitive, expressive. It was gratifying to watch the kids master new skills and learn to negotiate relationships. I liked the work even when a child in my care became angry or unhappy; I wanted to figure out the source of their difficulty and help guide them to a place of greater peace and comfort.

I quickly learned I was powerless to make some of the problems these kids faced go away. Like four-year old Frankie, a blondish white kid with a close-cropped haircut and a strong, compact body, who would come into the first center where I worked on a Monday morning, ready to raise cane. One of the veteran teachers recounted that Mondays were Frankie’s worst days, because every Sunday, his mother would have him all dressed and ready for his dad to pick him up. And then as often as not, his dad wouldn’t show. The challenge of such painful situations drew me deeper into the work.

As I moved from newcomer to a more experienced teacher of young children, and moved from Cambridge to Jamaica Plain to Dorchester, I grew dissatisfied with some of the practices that were commonplace among my co-workers. Many other teachers, to my way of thinking, were too quick to resort to punitive methods to enforce compliance with behavioral expectations. I found myself looking for alternative ways to approach the problems that arose in social interaction and group dynamics. Fortunately, other teachers were usually open to my suggestions.

For example, at the center in Dorchester, we had three “Big Wheels,” plastic cars in which kids could pedal around the yard during outdoor playtime. The three of us teachers (for eighteen kids) found ourselves spending an inordinate amount of time admonishing kids to be more careful in their driving habits as they careened around near the sandbox, the climbing structures, and other activities that were taking place, We also had to take names and monitor whose turn was next, as lots of kids wanted turns. Instead of having relaxed interactions in support of the play activities, at least one of us had to be occupied looking at their watch, to signal the current riders their time was almost up and tell the next in line to be ready for their turn. When that didn’t work, we made threats about losing future riding privileges if someone didn’t comply.

After consulting with my two co-teachers, I showed up one day with a bunch of those off-white computer keypunch cards that were in wide use in the 1970s. They were made of durable card stock. We asked each child to decorate one of these cards on both sides and print their name on it (they were four and five, and we could help with the name for anyone who was still mastering that skill). We then punched a hole in the top and put a strand of colorful yarn through each card, allowing them to hang them around their necks.

“These are your driver’s licenses,” we announced. “Do not take them home.” We installed a large hook near the door that exited to the yard. If you wanted to ride a Big Wheels, you must find your license (good for practicing name recognition) and wear it. “You can’t drive without a license.”

One of us teachers would bring a one-hole punch out to the playground. If you were driving recklessly, if you were too slow to comply with a request to give your car to the next person waiting, or if you otherwise committed an offense while driving, we would punch a hole in your license. The first two punches would be warnings, and the third would mean your license was suspended—moved to a hook much higher on the wall that only the grownups could reach. You could get it back after three days, so long as you sat down with one of the teachers and made a commitment to be a more responsible and cooperative driver.

The licenses were a huge hit! Some kids wore them outside even if they had no interest in the Big Wheels. For those who did drive the Big Wheels, the licenses (and the threat of that one-hole punch, I guess) brought out a level of cooperation we had never witnessed. We stopped wasting so much time monitoring the Big Wheels drivers and could spend more of our time interacting in a more relaxed and pleasurable way with the children engaging in other activities. We eventually got an oven timer with a loud bell, which children could set for the requisite amount of time when there were kids waiting to ride. They would hear the “ding” and transition to the next rider with minimal intervention from the teachers.

Only rarely did we have to use the one-hole punch, and only once do I recall making the third punch and having to impose the license suspension. The children largely embraced the new system. The one boy who had to forfeit his license was upset but did not accuse us of being unfair.

The whole transformation was a great example of moving “From policing to participation,” as described three decades later in a 2004 article of that title by Carol Ann Wien, a professor of early childhood education at York University in Toronto, published in Young Children, the journal of the National Association for the Education of Young Children. I only became a consumer of that journal and of other research literature in the field after going back to graduate school in the 1990s. It was affirming to see that many practices I instituted in the 1970s were consistent with the literature related to good practices—even literature that would not be published until decades later.

No matter how much the work attracted me, however, I could not look away from the fact that we were paid poverty wages. If day care workers were lucky back then, they got two weeks’ paid vacation after working for a year. No one in the field back then, so far as I could tell, ever had a conversation about retirement benefits. And only a few of the centers offered health insurance. (None of mine ever did.)

My lack of health insurance is one reason I ended up asking around about a chiropractor. The other reason was that my favorite sports hero was Roberto Clemente, the great outfielder and outstanding hitter on the Pittsburgh Pirates. If he had lived to retirement, instead of giving up his life on New Years’ Day, 1973, while ferrying supplies from Puerto Rico to the earthquake-stricken people of Nicaragua, he was planning a second career as a chiropractor.

I used to come home from meetings, sitting on the floor in Roy’s apartment, or Dell’s apartment, or Nancy’s apartment, or Johnny’s apartment, and my back would feel stiff for a while. But I would walk around, and it would feel better by the time I went to bed. Or if not, then it would feel better by the time I woke up in the morning.

Until one morning my back didn’t feel better. It felt worse. Then came those terrible times when I was home from work, or going to work in a compromised physical state.

By the time I met Delilah, things had improved somewhat. I wasn’t having severe pain or missing work. My chiropractic treatment and my commitment to the daily stretching routine seemed to have helped a lot. But the whole experience had been quite chastening. I had gone to an orthopedist who had taken X-rays and found nothing visible that he could treat. The woman who drove the bus for our childcare center had talked in my presence about going to a chiropractor; I took a chance and asked her about it. Dr. Anderson turned out to be a middle-aged white guy who came across as calm and authoritative. That was the origin of my first stretches and the routine of taking hot baths and lying supine every day.

My morning stretching routine would soon expand beyond Dr, Anderson’s three exercises that required barely more than five minutes. By the time I was in my first marriage in the 1980s, a second chiropractor—one I met through a woman I knew who used to smoke weed with him–had given me some additional stretches to add to my routine and had prescribed orthotics for me to wear in my shoes. By that point I needed a good 20 minutes each morning. I did some exercises lying on my back, some on my hands and knees, some standing, and some pushing against a wall.

I left Boston at age 42 for graduate school in Champaign, Illinois, in 1991. There I found another chiropractor, this one through someone I met in the local arts community. Over the following years, I needed to redress pains or stiffness in the neck, the back, the I/T band, the Achilles heel, the tennis elbow, and the golfer’s elbow (though I have never once golfed in my life). I had become an avid participant in aerobics classes, and as I discovered certain warm-up or cool-down stretches that helped me release tension, I would embed them into my routine.

By the time I finished my Ph,D, in special education in 1997, my morning routine took 30 to 35 minutes. I was still doing it every single morning without fail, before I had coffee or breakfast or brushed my teeth or anything. No matter if I was attending a conference and staying in a hotel or meeting up with my extended family for Rosh Hashanah.

Once I finished my degree, I moved back East to southwestern Vermont and then Berkshire County, Massachusetts. I got remarried and soon became a father. There were more aerobics instructors, another orthopedic specialist, another chiropractor. And at least one more new diagnosis related to parenting an infant son: my doctor called it nursemaid’s elbow. Around that same time, as I was turning 50, I learned the importance of resistance training. I purchased some 15- and 20-pound weights and incorporated upper body work at the end of my stretching routine. I heard it was good not to lift every day; my lifting days have been Mondays, Thursdays, and Saturdays ever since.

During prenatal classes before our son was born. I learned about an exercise that women preparing for childbirth are encouraged to do–they’re called kegels, . The birthing educator said, “It’s not a bad idea for you men either, if you want to avoid issues with incontinence later in your life.” It sounded good to me, so I started doing kegels every morning, right before the abdomenal crunches. In 2007, I was diagnosed with prostate cancer. My urologist explained the options that I should explore–open surgery, robotic-laparoscopic surgery, radioactive seeds. He said there was one intervention he wanted me to begin immediately, even before deciding on a course of treatment. “I want you to begin doing exercises that are called kegels.” He was starting to explain what they are. “Doctor,” I cut him off, “I don’t know if you’ve ever had a patient in my circumstances tell you this before, but I’ve been doing kegels every morning for the last seven years.” He may not have believed me. But after the surgery (I chose the laparoscopic-robotic version), I saw that I had zero issues of incontinence. I quietly sent my gratitude to my birthing educator out into the cosmos.

For five decades, no matter where I lived or where I spent the night, I found a place on the floor or on a rug or carpet or a mat to carry out my stretching routine as soon as I got up in the morning. My brothers and sisters and their kids got used to stepping around me when we would rent a house annually together for a week in Pawley’s Island, South Carolina Cats and dogs and toddlers found me an object of curiosity when I’ve stayed at the homes of friends—not unusual in their experience for a grownup to get down on the floor to interact with them, but for someone to be down on the floor and act completely disinterested in them, and quite vulnerable to being crawled or walked upon—that was the surprise. (It was mostly the felines or the young humans who welked or crawled or rolled onto me, not so much the canines, who merely sniffed around me at close range.)

At age 74, my routine runs 45 to 50 minutes four days a week, and a full hour on the three days I add the resistance training. I made the most recent additions to my repertoire just a couple of months ago, when I saw a physical therapist for a new lower back pain. She gave me three new stretches; not surprisingly, I had already been doing one of them for decades, but I inserted the other two into logical places in my daily sequence.

Outside of professional dancers or athletes, I have known of very few people who are as committed to daily stretching as I am. I missed two days of stretching when I first experienced the symptoms of Covid 19 in 2021. Before that I have to go back to 2015, when I broke my collarbone in a bike crash and missed one day when I was kept overnight in the hospital. Outside of those occasions, my stretching has been a seven days per week proposition. I’ve heard it said that when you form a habit, you don’t need motivation, and that’s the way it is with my stretching. It doesn’t require any motivation; it’s just what I do.

Delilah only dated my housemate Dave a handful of times. I don;’t know anything about her trajectory in the years that followed. But I have never forgotten the rest of that conversation I was recounting, in my bedroom in 1974.

I had questioned why she was making such a big deal of my commitment to my stretching. “Just think how flexible you will be in the years to come. If you keep up with these daily exercises, “ she opined. “When you’re an old man, you’re going to look back and be thankful you had this back problem. If you keep up this commitment, and keep doing these exercises, it’s going to be great for your conditioning,” she said cheerfully. I was quiet, Was she looking for a way to joke about my situation?

“You’re going to be such a flexible old man!” She said it with a smile, in a breathy kind of early-morning voice. It sounded kind of flirtatious. But also, sincere. “You won’t be one of those decrepit old guys, Dale. You’ll still be quite a catch.”

I realized it wasn’t a joke. It was a courteous person’s attempt, a very sweet attempt, to help me find a silver lining in an obviously bad situation.

I never forgot what she said. Now I am the old man that Delilah hypothesized. She was right: There is no way I would have embraced this routine, with this consistency of commitment, without those terrible debilitating challenges I faced in my early twenties.

The Delilah in the Bible did not speak words that were prophetic, so far as I recall. But the one I call Delilah did. I couldn’t be more thankful I had those back problems in my youth. They set me on the right path toward healthy aging.

Dale Borman Fink retired in 2020 from Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, MA, where he taught courses related to research methods, early childhood education, special education, and children’s literature. Prior to that he was involved in childcare, after-school care, and support for the families of children with disabilities. Among his books are Making a Place for Kids with Disabilities (2000) Control the Climate, Not the Children: Discipline in School Age Care (1995), and a children’s book, Mr. Silver and Mrs. Gold (1980). In 2018, he edited a volume of his father's recollections, called SHOPKEEPER'S SON.

I’m sure Delilah was right–that your commitment to self-care would serve you well. That is a very impressive accomplishment to have struggled with your back (and other bothersome conditions) for so long but still have managed to keep yourself active and living well. Congratulations. Thanks also for the description of some of the rewards and challenges of early childhood education–very inspiring. I’m sure the children thank you, whether they realize it or not.

Thanx for sharing this story Dale.

I knew what a dedicated early childhood educator you were, and am impressed by the books you’ve published.

Over my years working in schools I’ve long admired my colleagues who were good teachers and dedicated to the kids, but especially those who were wonderfully creative as well, as you obviously were.

I love the drivers licenses for the kids, and the concert of moving from policing to participation. I smile at folks who think teaching – and especially teaching little kids – is easy. Those who do it well know it’s not and often involves blood, sweat and tears.

And your discipline in handling your pain is admirable. Your story about Delilah reminds me of Leonard Cohen’s lyric,

“She tied you to a kitchen chair/ She broke your throne and she cut your hair.”

I love that the story put you in mind of Leonard Cohen’s lyric! That’s a first for me.

You’ve given us two parts to this story, Dale. One is the genesis of your back problems – your work at daycare centers, the wonders that you accomplished there (I love the idea of the “driver’s license” for the “Big Wheels”; so clever and functional) and your work to organize the workers, requiring long hours of uncomfortable floor sitting. The other part is the actual ways in which you’ve learned to care for your back and the routine you’ve maintained for DECADES! Kudos to you for that discipline.

Like you, I’ve had back problems most of my life, but have not been as troubled by it, nor as committed to good physical hygiene, but six months before turning 60 (so during the summer of 2012), I decided to lose weight and get into shape. I joined a gym, got a trainer who worked on my nutrition as well as a program of physical activity (most of which I do in a gym, though during lock-down, I took Zoom classes with favorite teachers). I did lose 18 pounds (some of it has returned, but not most) and I became a gym rat, going 4 or 5 days a week, and I continue to stream those favorite Zoom classes on two days at home (on weekends, when the gym is always so busy). I take a variety of classes, working on core, muscle tone and some aerobics. But a few days a week, I do the workout laid out for me by that trainer, which includes a half hour aerobic workout, then machines for strength. Having done mat Pilates for a dozen years or so, my back problems are greatly reduced, and I will foam-roller my back when it starts to hurt. I admire your discipline. Right now I’m recovering from ankle surgery (5 weeks out). I just started PT this week and am determined to be out the boot as quickly as possible, so am following his instructions precisely and doing all the exercises twice a day. It is a form of religion, isn’t it?

Thanks, Betsy, foryour personal story and for the analysis of my story’s structure. I have been using the opportunity of Retrospect in recent months to “play” with narrative structure. In this one, I began the first draft with the whole conversation with Delilah being presented in the opening paragraphs, but in a later draft I subdivided it and moved her prophetic words to the very end. I also enjoyed providing some real substance (i.e., narrative about the driver licenses) so that my work in daycare would be more than just a “back drop.” There was certainly the risk of slowing down the main thread of the story too much, but I decided to take that risk. I will be appreciative of any future comments on these kinds of story issues. Thanks!

Well done, Dale, once again. The theme — the important turning-point message — shines through, but I also appreciate learning the context — learning more about you. And I love the humor, e.g., you wanting to appear strong and masculine and Delilah giving you a haircut!

Thanks! I’m glad you appreciated the humor in that passage. Also, it sounds like you thought the long-ish descriptions of the “context” did not distract too much from the major thread of the story. That’s good to know; I’ve been trying to play with narrative structures and time sequences and overlaying one narrative thread on another, and I invite your further comments in that regard, on this or any other story. (And this invite goes to anyone else who is reading this comment.)