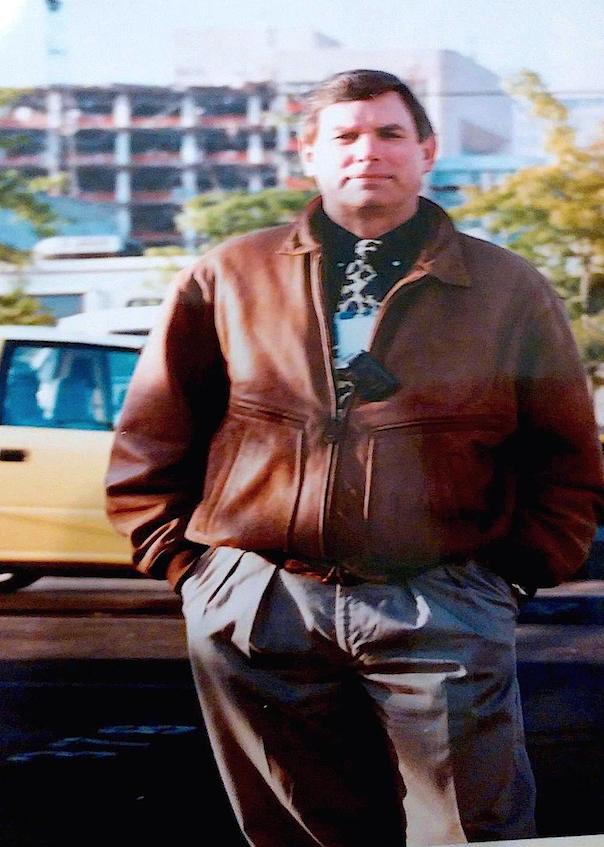

On Assignment, the Murrah Federal Building behind me, April 1995

It was a warm and sunny March afternoon in 1995, and I was in a reflective mood as I drove my Isuzu Rodeo north on Arizona’s Interstate 17 through the Coconino National Forest. The city of Flagstaff, one of America’s best-kept secrets, loomed about 20 miles ahead.

Sometimes an interstate exit can lead you to a new life, even in the midst of tragedy.

I looked forward to seeing Flagstaff again, remembering how beautiful its setting was amid the foothills, pine trees, and cooler temperatures of northern Arizona. Flagstaff is the gateway city to the Grand Canyon, which is 45 minutes to the north. Unlike the stereotypical Arizona town, Flagstaff experiences a four-season climate.

Running to and from

I was on a self-imposed leave from my faculty post at Boston College, trying to deal with a deeply painful experience. I had been driving north about three hours after leaving the obscure town of Apache Junction earlier that morning.

Apache Junction is the trailhead town of the Superstition Mountains, and I had just spent a week trying to lose or find myself — I wasn’t sure which — exploring the rugged mountains on horseback.

Apache Junction is the trailhead town of the Superstition Mountains, and I had just spent a week trying to lose or find myself — I wasn’t sure which — exploring the rugged mountains on horseback.

So now I I was going … well, that was the question, wasn’t it? I wasn’t sure where I was going.

Dark Moments

At this point in my life I was a mobile human wreck of a 49-year-old man in the middle of an emotional, midlife crisis that had been my worst nightmare come true and which had already caused me to flirt briefly with the idea of suicide a couple months before.

Gratefully, that moment passed without incident.

Here on this Arizona highway, I was following instincts, subconsciously trusting them to show me where to go. But on this bright sunny day on a four-lane highway, it was like I was just feeling my way along in the dark on a country road.

I had the feeling I should exit onto I-40 when I got there, but was unsure why or whether to turn west or east. I just felt it would somehow be an important decision.

I had the feeling I should exit onto I-40 when I got there, but was unsure why or whether to turn west or east. I just felt it would somehow be an important decision.

I had just spent a week in an otherworldly wilderness, doing something completely different from my Boston routine, something designed to remove me from my nightmarish reality and allow me to grope for my life’s reset button. Was that button just ahead at the I-40 interchange?

A lost love

The dark reality tearing at me was that I had lost the woman we’ll call Donna and, along with her, 16 years of an all-consuming relationship and marriage spent in heaven, followed by its final year in the flames of hell. The problem was, even when it was at its worst, I couldn’t imagine life without her.

Thinking of the times she wept, I still tasted salt.

I wasn’t yet 50, and I had already lived and worked in six states. I’d been commuting from my Boston job to our home in a large midwestern city for the past two years. I realized, over time, that my wanderlust had contributed to Donna’s disenchantment with me, as she became much more sedentary when we moved from Boston. She was tired of changing addresses. She loved her television news anchoring career, and she was good at her job.

She was tired of changing addresses. She loved her television news anchoring career, and she was good at her job.

A fearful freedom

Not far to that exit now. I scanned the desert, the multicolored mesas, and distant mountains that were all laid out around me as I pushed toward Flagstaff. Past that, who knew?

I supposed I’d figure it out when the time came. The liberty to do that, as well as the endless openness of Arizona, all enhanced my feelings of – and love for – freedom. Or, at least, the idea of freedom.

I was in a state of being free, yet I was also trapped in loneliness. When the Kris Kristofferson song, Me and Bobby McGee queued up on my CD player, the lyrics fit my mood perfectly. “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose,” Kris would croon in his slow, craggy voice.

I was a freaking mess.

Exit 171

My mind was still swirling as I approached Exit 171, and I had this feeling I wasn’t nearly ready to return to Boston. I was strongly considering going the opposite direction on I-40, west to California. I’d been to the mountains, so why not the ocean next?

I realized, though, that turning east didn’t necessarily mean I had to return to Boston. In between Arizona and Massachusetts was my native state of Oklahoma where Mom, Dad, and my sister still lived.

Within the span of the next mile, something inside pulled me back to my Oklahoma roots and suggested that’s where I’d find my reset button.

I turned east. I was going home.

The road ahead

I could not know, at that moment, what would lie ahead for me in Oklahoma City. I could not know that my life would start over on April 19, 1995, the same day life would end tragically for 168 other innocent souls.

The moment I decided to turn right instead of left onto I-40 would be the moment that changed my life forever.

I’ve sometimes wondered if Timothy McVeigh was already assembling parts for his bomb as I headed to Oklahoma City. I’ve also wondered how — or why — I could/should find new life amid so much death?

Haunting question

I’ve given that second question a lot of thought since then. I think the answer has to do with the collision of my personal pain and the collective pain that would soon surround me. And perhaps it also had to do with the clarity that comes from writing about others who are experiencing an even greater degree of pain than I was.

Going back to work

In a few weeks, the earth would move in Oklahoma City and I would return to my old life as a journalist reporting on tragedy. That job has a way of putting any reporter’s own pain in perspective. That happened to me, and, I was able to release my own pain in writing about the pain of Oklahoma City.

On April 19, when I offered my skills and experience as a reporter to an Oklahoma City newspaper to cover the bombing, I was also giving myself a way to make connections with other grieving people. The shared experience of grief made us all feel less alone in Oklahoma City. I came to experience a new-found pride in the people of this state that i had been so eager to leave when I was in my 20s.

Regained confidence

Realizing I could contribute by finding answers to questions these grieving survivors wanted, made me feel like I still had something positive to offer. I began feeling better about myself and more confident that I could emerge from my own pain a stronger person. Just like these folks were doing in my native state.

Twenty-seven years later, I’m still sickened that the Oklahoma City bombing happened, but I’m glad I was able to be with my people there when it did.

So that turn I made back in Flagstaff? It was the right choice.

I am a writer, college professor, and author of several nonfiction books, including three on the decade of the 1960s. Several wonderful essays of gifted Retrospect authors appear in my book, "Daily Life in the 1960s."

Thanx Jim for sharing your very personal story!

Your decision to go home, and then to use your journalistic skills to share the tragedy of the bombing victims actually helped you find a new direction and to change your own life – bravo!

Thanks, Dana. Strange how that works, isn’t it? When I think about the bombing and how it affected me, two statements come to mind from literary works. The upbeat thought was offered by the character Tom Wingo is Prince of Tides when he reflects, “It is the mystery of life that sustains me now.” The more somber one is from Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyl and Mr. Hyde: “If we must learn wisdom tomorrow from violence today, then who can expect there will be a tomorrow?”

Thanks Jim, for this inspirational story! You show us that even the most horrifying events can have some good effects if you know where to look. And that there’s no place like home!

Thanks, Suzy. You’re right, on both points!

What an amazing story, Jim. And, as noted, just so deeply personal. So thank you for the courage of sharing it.; I am not sure I could do the same.

I often use the phrase “misery loves company,” but usually in semi-jest, as is my wont. But, in your own life, it was obviously the source of a very real connection with the grieving citizens of Oklahome City. And, clearly, this was a source of healing for you from your own personal loss. And I sense it helped them with their own healing as well, to your great credit.

Thank you, John. The greatest oddity of my life was that I began the healing process by writing about so many others who had just been plunged into raw grief. I do believe it’s true that we at least learned from each other; if not helped each other. I will always remember the note a reader wrote me about one story I had written. My story described a memorial held on the Murrah Building rubble two weeks after the bombing. My goal was to bring readers to the scene; for them to experience what I felt. The note was from a reader who had lost a loved one in the blast. It said simply: “Thank you so much. You made me feel like I was there.” That note meant a lot to me, and I still have it.

This is a powerful story, Jim. Choosing to go home at such a critical time helped you put things in perspective and use your personal pain to reach out to others in pain.

Thanks, Laurie. I guess home is the answer for a lot of troubles in life.

I remember that day so well, Jim, as we were running the Boston Marathon here (I live by Heartbreak Hill, at the edge of the Boston College campus, from which you had fled). So we sort of converged on that day.

Your turn east on I 40 toward “home” was, indeed, a moment that changed your life. You’ve shared your pain and redemption with great feelings about your own narrative, but it was just that which allowed you to connect so strongly with what happened to the innocent others at the bombed building on April 19, 1995. Your shared sense of grief and loss that you brought to their story allowed the public to connect and allowed you to heal. It was journalism at its finest.

Thanks so much, Betsy. That’s kind of you. In Oklahoma City, my soul was stirred and arose like a Phoenix from the ashes of the bombing. The privilege of getting to know the people there and writing their stories enabled that to happen.

First of all, I really appreciate your writing skill—what a great job weaving together different strands of directions in life. And you share enough personal pain to make it real without going unbearably deep—but certainly enough to make it clear why you found special meaning in your work as a journalist for the Oklahoma bombing disaster. How human we all are, and how appropriate to reconnect in healing. Wonderful story and thanks for the insights.

Thanks so much, Khati. This was a difficult one to write and is actually a shortened excerpt from a much larger memoir I’m writing, which is even tougher. This is a new genre for me and I’m feeling my way along. Your kind comments help!

A very powerful story, and written with grit, eloquence, and grace. The way you allowed your personal torment to connect you with the people who suffered from the OKC bombing reminds me of one of Joe Biden’s best qualities–his ability to view the losses of others through the lens of his own losses–first of his wife and younger children, and then later, of his grown son Beau.

Thank you so much, Dale, for your kind comments on this. You’re right about the collision of my pain with Oklahoma City’s. I doubt if I would have ever even offered up my services as a journalist if I wasn’t already feeling such acute pain and realizing these people were looking for answers, just as I was. It was a strong connection from the get-go, and I allowed it to fuel my writing and tell the stories in ways I never had before. I never veered from the facts, but I realized that so much of what I saw, heard deserved more than traditional, arms-length journalistic formats. I also realized that the emotional reaction of families and survivors WAS my story. I wasn’t involved in the criminal aspect or the (brief) hunt for suspects. My focus was on the people in and around ground zero. That meant reporting on emotions, and feeling pain myself helped me in understanding their story.

Powerfully self-revelatory, Jim. Sharing such profound inner pain is hard as hell, even years after. We all feel we should have been stronger, tougher and more resilient. Admitting and sharing times we were not is wrenching.

Your trip to the Superstition Mountains reminded me of the song “Coast of Marseilles” by Jimmy Buffett.

Thanks, Dave. Writing about it does have a way of transporting you back to those feelings but, as you know, writing about it is also therapeutic. Writing these Retrospect posts is a lot like journaling. You just share those stories with other writers, and that makes it less foreboding.